|

Topics

Introduction

Problems Freedom Knowledge Mind Life Chance Quantum Entanglement Scandals Philosophers Mortimer Adler Rogers Albritton Alexander of Aphrodisias Samuel Alexander William Alston Anaximander G.E.M.Anscombe Anselm Louise Antony Thomas Aquinas Aristotle David Armstrong Harald Atmanspacher Robert Audi Augustine J.L.Austin A.J.Ayer Alexander Bain Mark Balaguer Jeffrey Barrett William Barrett William Belsham Henri Bergson George Berkeley Isaiah Berlin Richard J. Bernstein Bernard Berofsky Robert Bishop Max Black Susan Blackmore Susanne Bobzien Emil du Bois-Reymond Hilary Bok Laurence BonJour George Boole Émile Boutroux Daniel Boyd F.H.Bradley C.D.Broad Michael Burke Jeremy Butterfield Lawrence Cahoone C.A.Campbell Joseph Keim Campbell Rudolf Carnap Carneades Nancy Cartwright Gregg Caruso Ernst Cassirer David Chalmers Roderick Chisholm Chrysippus Cicero Tom Clark Randolph Clarke Samuel Clarke Anthony Collins August Compte Antonella Corradini Diodorus Cronus Jonathan Dancy Donald Davidson Mario De Caro Democritus William Dembski Brendan Dempsey Daniel Dennett Jacques Derrida René Descartes Richard Double Fred Dretske Curt Ducasse John Earman Laura Waddell Ekstrom Epictetus Epicurus Austin Farrer Herbert Feigl Arthur Fine John Martin Fischer Frederic Fitch Owen Flanagan Luciano Floridi Philippa Foot Alfred Fouilleé Harry Frankfurt Richard L. Franklin Bas van Fraassen Michael Frede Gottlob Frege Peter Geach Edmund Gettier Carl Ginet Alvin Goldman Gorgias Nicholas St. John Green Niels Henrik Gregersen H.Paul Grice Ian Hacking Ishtiyaque Haji Stuart Hampshire W.F.R.Hardie Sam Harris William Hasker R.M.Hare Georg W.F. Hegel Martin Heidegger Heraclitus R.E.Hobart Thomas Hobbes David Hodgson Shadsworth Hodgson Baron d'Holbach Ted Honderich Pamela Huby David Hume Ferenc Huoranszki Frank Jackson William James Lord Kames Robert Kane Immanuel Kant Tomis Kapitan Walter Kaufmann Jaegwon Kim William King Hilary Kornblith Christine Korsgaard Saul Kripke Thomas Kuhn Andrea Lavazza James Ladyman Christoph Lehner Keith Lehrer Gottfried Leibniz Jules Lequyer Leucippus Michael Levin Joseph Levine George Henry Lewes C.I.Lewis David Lewis Peter Lipton C. Lloyd Morgan John Locke Michael Lockwood Arthur O. Lovejoy E. Jonathan Lowe John R. Lucas Lucretius Alasdair MacIntyre Ruth Barcan Marcus Tim Maudlin James Martineau Nicholas Maxwell Storrs McCall Hugh McCann Colin McGinn Michael McKenna Brian McLaughlin John McTaggart Paul E. Meehl Uwe Meixner Alfred Mele Trenton Merricks John Stuart Mill Dickinson Miller G.E.Moore Ernest Nagel Thomas Nagel Otto Neurath Friedrich Nietzsche John Norton P.H.Nowell-Smith Robert Nozick William of Ockham Timothy O'Connor Parmenides David F. Pears Charles Sanders Peirce Derk Pereboom Steven Pinker U.T.Place Plato Karl Popper Porphyry Huw Price H.A.Prichard Protagoras Hilary Putnam Willard van Orman Quine Frank Ramsey Ayn Rand Michael Rea Thomas Reid Charles Renouvier Nicholas Rescher C.W.Rietdijk Richard Rorty Josiah Royce Bertrand Russell Paul Russell Gilbert Ryle Jean-Paul Sartre Kenneth Sayre T.M.Scanlon Moritz Schlick John Duns Scotus Albert Schweitzer Arthur Schopenhauer John Searle Wilfrid Sellars David Shiang Alan Sidelle Ted Sider Henry Sidgwick Walter Sinnott-Armstrong Peter Slezak J.J.C.Smart Saul Smilansky Michael Smith Baruch Spinoza L. Susan Stebbing Isabelle Stengers George F. Stout Galen Strawson Peter Strawson Eleonore Stump Francisco Suárez Richard Taylor Kevin Timpe Mark Twain Peter Unger Peter van Inwagen Manuel Vargas John Venn Kadri Vihvelin Voltaire G.H. von Wright David Foster Wallace R. Jay Wallace W.G.Ward Ted Warfield Roy Weatherford C.F. von Weizsäcker William Whewell Alfred North Whitehead David Widerker David Wiggins Bernard Williams Timothy Williamson Ludwig Wittgenstein Susan Wolf Xenophon Scientists David Albert Philip W. Anderson Michael Arbib Bobby Azarian Walter Baade Bernard Baars Jeffrey Bada Leslie Ballentine Marcello Barbieri Jacob Barandes Julian Barbour Horace Barlow Gregory Bateson Jakob Bekenstein John S. Bell Mara Beller Charles Bennett Ludwig von Bertalanffy Susan Blackmore Margaret Boden David Bohm Niels Bohr Ludwig Boltzmann John Tyler Bonner Emile Borel Max Born Satyendra Nath Bose Walther Bothe Jean Bricmont Hans Briegel Leon Brillouin Daniel Brooks Stephen Brush Henry Thomas Buckle S. H. Burbury Melvin Calvin William Calvin Donald Campbell John O. Campbell Sadi Carnot Sean B. Carroll Anthony Cashmore Eric Chaisson Gregory Chaitin Jean-Pierre Changeux Rudolf Clausius Arthur Holly Compton John Conway Simon Conway-Morris Peter Corning George Cowan Jerry Coyne John Cramer Francis Crick E. P. Culverwell Antonio Damasio Olivier Darrigol Charles Darwin Paul Davies Richard Dawkins Terrence Deacon Lüder Deecke Richard Dedekind Louis de Broglie Stanislas Dehaene Max Delbrück Abraham de Moivre David Depew Bernard d'Espagnat Paul Dirac Theodosius Dobzhansky Hans Driesch John Dupré John Eccles Arthur Stanley Eddington Gerald Edelman Paul Ehrenfest Manfred Eigen Albert Einstein George F. R. Ellis Walter Elsasser Hugh Everett, III Franz Exner Richard Feynman R. A. Fisher David Foster Joseph Fourier George Fox Philipp Frank Steven Frautschi Edward Fredkin Augustin-Jean Fresnel Karl Friston Benjamin Gal-Or Howard Gardner Lila Gatlin Michael Gazzaniga Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen GianCarlo Ghirardi J. Willard Gibbs James J. Gibson Nicolas Gisin Paul Glimcher Thomas Gold A. O. Gomes Brian Goodwin Julian Gough Joshua Greene Dirk ter Haar Jacques Hadamard Mark Hadley Ernst Haeckel Patrick Haggard J. B. S. Haldane Stuart Hameroff Augustin Hamon Sam Harris Ralph Hartley Hyman Hartman Jeff Hawkins John-Dylan Haynes Donald Hebb Martin Heisenberg Werner Heisenberg Hermann von Helmholtz Grete Hermann John Herschel Francis Heylighen Basil Hiley Art Hobson Jesper Hoffmeyer John Holland Don Howard John H. Jackson Ray Jackendoff Roman Jakobson E. T. Jaynes William Stanley Jevons Pascual Jordan Eric Kandel Ruth E. Kastner Stuart Kauffman Martin J. Klein William R. Klemm Christof Koch Simon Kochen Hans Kornhuber Stephen Kosslyn Daniel Koshland Ladislav Kovàč Leopold Kronecker Bernd-Olaf Küppers Rolf Landauer Alfred Landé Pierre-Simon Laplace Karl Lashley David Layzer Joseph LeDoux Gerald Lettvin Michael Levin Gilbert Lewis Benjamin Libet David Lindley Seth Lloyd Werner Loewenstein Hendrik Lorentz Josef Loschmidt Alfred Lotka Ernst Mach Donald MacKay Henry Margenau Lynn Margulis Owen Maroney David Marr Humberto Maturana James Clerk Maxwell John Maynard Smith Ernst Mayr John McCarthy Barbara McClintock Warren McCulloch N. David Mermin George Miller Stanley Miller Ulrich Mohrhoff Jacques Monod Vernon Mountcastle Gerd B. Müller Emmy Noether Denis Noble Donald Norman Travis Norsen Howard T. Odum Alexander Oparin Abraham Pais Howard Pattee Wolfgang Pauli Massimo Pauri Wilder Penfield Roger Penrose Massimo Pigliucci Steven Pinker Colin Pittendrigh Walter Pitts Max Planck Susan Pockett Henri Poincaré Michael Polanyi Daniel Pollen Ilya Prigogine Hans Primas Giulio Prisco Zenon Pylyshyn Henry Quastler Adolphe Quételet Pasco Rakic Nicolas Rashevsky Lord Rayleigh Frederick Reif Jürgen Renn Giacomo Rizzolati A.A. Roback Emil Roduner Juan Roederer Robert Rosen Frank Rosenblatt Jerome Rothstein David Ruelle David Rumelhart Michael Ruse Stanley Salthe Robert Sapolsky Tilman Sauer Ferdinand de Saussure Jürgen Schmidhuber Erwin Schrödinger Aaron Schurger Sebastian Seung Thomas Sebeok Franco Selleri Claude Shannon James A. Shapiro Charles Sherrington Abner Shimony Herbert Simon Dean Keith Simonton Edmund Sinnott B. F. Skinner Lee Smolin Ray Solomonoff Herbert Spencer Roger Sperry John Stachel Kenneth Stanley Henry Stapp Ian Stewart Tom Stonier Antoine Suarez Leonard Susskind Leo Szilard Max Tegmark Teilhard de Chardin Libb Thims William Thomson (Kelvin) Richard Tolman Giulio Tononi Peter Tse Alan Turing Robert Ulanowicz C. S. Unnikrishnan Nico van Kampen Francisco Varela Vlatko Vedral Vladimir Vernadsky Clément Vidal Mikhail Volkenstein Heinz von Foerster Richard von Mises John von Neumann Jakob von Uexküll C. H. Waddington Sara Imari Walker James D. Watson John B. Watson Daniel Wegner Steven Weinberg August Weismann Paul A. Weiss Herman Weyl John Wheeler Jeffrey Wicken Wilhelm Wien Norbert Wiener Eugene Wigner E. O. Wiley E. O. Wilson Günther Witzany Carl Woese Stephen Wolfram H. Dieter Zeh Semir Zeki Ernst Zermelo Wojciech Zurek Konrad Zuse Fritz Zwicky Presentations ABCD Harvard (ppt) Biosemiotics Free Will Mental Causation James Symposium CCS25 Talk Evo Devo September 12 Evo Devo October 2 Evo Devo Goodness Evo Devo Davies Nov12 |

Albert Einstein

Einstein saw a wave randomly "collapse" twenty years before there was a "wave function" and the Schrödinger wave equation. He discovered the existence of indeterministic chance as a "weakness" in quantum theory over a decade before Heisenberg published his uncertainty principle.

Since the validity of any theory rests on its experimental confirmation, as Einstein knew very well, we can say that the extraordinary confirmation of quantum mechanics, especially its probabilistic nature, makes it the best supported theory in the history of science, but nevertheless it is a statistical theory.

Paradoxically, ironically perhaps, and even tragically, only a handful of scientists and philosophers recognize the full range of Einstein's contributions, primarily because he disavowed his own quantum discoveries as contrary to his fundamental beliefs about the workings of the universe. Few of us are immune to the power of beliefs that prevent the acceptance of scientifically established facts. As exceptional a scientist as Einstein was, he was no exception there. Randomness was not his only concern, maybe not even his main concern, as we shall see. Quantum mechanics appears to conflict with special relativity, and its nonlocality may conflict with general relativity and Einstein's dream of a "unified field theory."

All his life, Einstein had grave doubts about field theories. They became more extreme in his later years, when he wrote

He deplored his discoveries. One can give good reasons why reality cannot at all be represented by a continuous field. From the quantum phenomena it appears to follow with certainty that a finite system of finite energy can be completely described by a finite set of numbers (quantum numbers). This does not seem to be in accordance with a continuum theory, and must lead to an attempt to find a purely algebraic theory for the description of reality. But nobody knows how to obtain the basis of such a theory.In principle, continuous field theories contain an infinite amount of information. The differential equations that describe classical physics in space and time assume there are an infinite number of infinitesimal points along any finite line segment. But Einstein saw that any finite volume (even the whole observable universe) can contain only a finite number of discrete quanta of matter or energy. Quantum mechanics can thus in principle be described with simpler difference equations in what Einstein described as an "algebraic" theory. Ludwig Boltzmann had shown that he could derive his entropy law assuming that space can be described as "coarse grained" into small enough discrete volumes, though still large enough to contain many particles. Quite apart from his great deterministic and continuous theories of special and general relativity, Einstein was one of the most important creators (both discoverer and inventor) of the indeterministic and discrete theory of quantum mechanics. In his 1905 paper on the light-quantum hypothesis and photoelectric effect, he quantized the radiation field, where Max Planck had only quantized the energy in his virtual oscillators. Einstein was first to see that electromagnetic radiation is particulate. And in his very next paper he proved the existence of atoms. In that one year he saw both matter and energy as particulate and how they are converted into one another, E = mc2. Einstein thus saw that both the material and the energetic universe have discrete and discontinuous properties! His 1905 paper on Brownian motion predicted sizes and motions for atoms that were confirmed just a few years later. And although he waited ten years to do so, Einstein stated unequivocally that quantum processes are fundamentally indeterministic, a matter of chance. "A weakness in the theory," he called it in 1916. He lamented at that time to his friend Michele Besso that he was the only scientist who believed in the reality of what we now call photons, "I do not doubt anymore the reality of radiation quanta, although I still stand quite alone in this conviction." On a careful reading of his 1905 photoelectric effect paper, we can see that Einstein was already concerned about faster-than-light actions, thirty years before his Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paper popularized the mysteries and paradoxes of quantum nonlocality and entanglement. We hope to show that many of today's controversies in the interpretations of quantum mechanics can be resolved by seeing these problems through Einstein's eyes. Despite his foundational work quantizing radiation, Einstein rarely gets any credit for his contributions to quantum mechanics. There are a number of important reasons for this, which lead historians of quantum theory to start with Planck's quantum of action, then jump over Einstein's 1905 papers and his 1909 work on wave-particle duality to Niels Bohr's "old quantum theory" of the atom in 1913. Today, Bohr's "quantum jump" of an electron between stationary states is described as emitting or absorbing a "photon" of energy hν. In actuality, Bohr fought against Einstein's light-quantum hypothesis and denied the existence of photons until the mid-1920's. Bohr's work in 1924 with H. A. Kramers and John Slater was the last defense of continuous, as opposed to discrete, radiation. The Bohr-Kramers-Slater theory claimed that energy was not conserved in each matter-radiation interaction, but only conserved statistically. Immediately, Einstein suggested multiple experiments to Walther Bothe that could disprove the BKS claim. In 1925, Bothe and Hans Geiger developed two experiments that disproved the BKS theory. At this point, Bohr finally accepted, though never enthusiastically, Einstein's light quanta as real, twenty years after Einstein's insight in his 1905 "miracle year." Besides quantizing light energy and seeing its interchangeability with matter, E = mc2, Einstein was the first scientist to see many of the most fundamental aspects of quantum physics, e.g., nonlocality and instantaneous action-at-a-distance (1905), wave-particle duality (1909), emission and absorption processes that introduce indeterminism and acausality whenever matter and radiation interact (1916-17.) He predicted the stimulated emission of radiation behind today's lasers, the indistinguishability of elementary particles with their strange quantum statistics (1925), and the nonseparability and entanglement of interacting identical particles (1935). Just because Einstein did not regard any of these discoveries as part of a fundamental "local" reality that Einstein wanted is no reason to deny him credit for them all. Einstein's description of wave-particle duality is as good as anything written today. He saw the relation between the wave and the particle as the relation between probable possibilities and the realization of one possibility as an actual event. He saw the wave spreading out in space and giving us the probability of finding a particle in different locations. Where Einstein saw the particle as concrete and material, he described the wave as a "ghostly field," which is exactly right according to the information interpretation of quantum mechanics. The wave is neither matter nor energy, but pure abstract information about locating concrete matter and energy. The information about probabilities and possibilities in the wave function is immaterial, but that abstract information has real causal powers. The wave's interference with itself predicts null points where no particles should be found. And experiments confirm that no particles are found there. Immaterial information is a kind of modern "spirit." Einstein also described the wave function as a ""guiding field" (Führungsfeld), an idea taken up later by Louis de Broglie as his "pilot waves." Following de Broglie, Schrödinger developed his equation that gives us the value of the wave function ψ at each point and describes how the probability-amplitude wave function moves through space deterministically. This restoration of some determinism was a brief bright moment for Einstein. He saw a possible return to a deterministic theory for quantum mechanics and his continuous field theory. But it was not to be, despite the large number of present-day physicists who are still pursuing Einstein's and Schrödinger's deterministic dreams, by denying indeterminism and "quantum jumping." The linearity of the Schrödinger wave equation produces the mysterious superposition of states and the projection postulate - the wave function "collapse." In a linear equation, the sum of two solutions is also a solution. Although the projection postulate is basically a formalization of Einstein's 1916 transition probabilities from an excited state to more than one lower state, although he had been first to see a light wave collapse into a photon that could eject an electron in his 1905 photoelectric effect paper, and although he had been first to proclaim ontological chance as a part of the quantum theory, it must have been a disappointment to Einstein to find that the determinism in Schrödinger's wave equation could only determine his probabilities and that ontological chance is still real. Einstein could never accept most of his quantum discoveries because they conflicted with his basic idea that nature is best described by a continuous field theory using partial differential equations that are functions of "local" variables, primarily the space-time four-vector of his general relativistic theory. Einstein's idea of a "local" reality is one where "action-at-a-distance" is limited to causal effects that propagate at or below the speed of light, according to his theory of relativity. Einstein believed that quantum theory, as good as it is (and he never saw anything better), is "incomplete." This is so, because its statistical predictions (phenomenally accurate in the limit of large numbers of identical experiments - "ensembles" Einstein called them), tell us nothing but "probabilities" about individual systems. Even worse, he saw that the wave functions of entangled two-particle systems predict faster-than-light correlations of properties between events in a space-like separation. He mistakenly thought this violated his theory of relativity. Although this was the heart of his famous EPR paradox paper in 1935, we shall see that Einstein was already concerned about faster-than-light transfer of energy and that he saw spherical light waves "collapsing" instantaneously in his very first paper on quantum theory. In most general histories, and in the brief histories included in modern quantum mechanics textbooks, the problems raised by Einstein are usually presented as arising after the "founders" of quantum mechanics and their Copenhagen Interpretation in the late 1920's. Modern attention to Einstein's work on quantum physics often starts with the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paper of 1935, when the mysteries of nonlocality, nonseparability, and entanglement are first clearly understood by Einstein's opponents. Physicists today think of quantum mechanics as beginning with the Heisenberg (particle) formulation and the Schrödinger (wave) formulation. The popular image of Einstein post-EPR is either in the role of critic trying to expose fundamental flaws in the "new" quantum mechanics or as an old man who simply didn't understand the new quantum theory. Both these images of Einstein are seriously flawed, as we shall see. Many histories of quantum theory, most starting from the Copenhagen perspective of Bohr, Heisenberg, Born, Jordan, and Pauli, focus on Einstein's failed attempts in debates with Bohr to challenge the uncertainty principle. EPR is described as failing to show that quantum mechanics is "incomplete." This is a verbal quibble. Quantum mechanics is indeed incomplete in that it cannot predict simultaneously the position and momentum of a particle, nor the "real" path of a particle between measurements. Most important, QM is only a statistical theory, as Einstein maintained. Its results are only confirmed by large numbers of identical experiments. Continuous matter and radiation only appear when we average over large numbers of discrete particles. Few histories point out that it was Einstein who over three decades invented (or discovered) nonlocality and entanglement, as well as the ontological chance in quantum mechanics that is the real basis of the acausality that Heisenberg later saw in his uncertainty principle.

The Light-Quantum Hypothesis (1905)

The Photoelectric Effect (1905)

Einstein had very strong reasons for imagining that light must be concentrated in a physically localized bundle of energy. He described it in section 8 of this same paper, explaining the photoelectric effect, the emission of electrons from surfaces illuminated by radiation. He wrote:

The usual conception, that the energy of light is continuously distributed over the space through which it propagates, encounters very serious difficulties when one attempts to explain the photoelectric phenomena, as has been pointed out in Herr Lenard's pioneering paper.Einstein shows here that the whole energy of an incident light quantum is absorbed by a single electron. Some of that energy is P, the work needed to escape from the metal. The rest is the kinetic energy E = ½ m v2 of the electron. Einstein's "photoelectric equation" is

E = hν - P

This equation predicts a linear relationship between the frequency of Einstein's light quantum hν, and the energy E of the ejected electron. It wasn't until ten years later that R. A. Millikan confirmed Einstein's photoelectric equation. Millikan nevertheless denied that it proved Einstein's radical but clairvoyant ideas about light quanta!

If the energy travels as a spherical light wave radiated into space in all directions, how can it instantaneously collect itself together to be absorbed into a single electron. Einstein already in 1905 sees something nonlocal about the photon and that there is both a wave aspect and a particle aspect to electromagnetic radiation. He will make those aspects more clear and in 1909 describe the wave-particle relationship more clearly than it is usually presented today, with all the confusion about whether photons and electrons are waves or particles or both.

Wave-particle duality (1909)

Einstein greatly expanded his light-quantum hypothesis in a presentation at the Salzburg conference in September, 1909. He argued that the interaction of radiation and matter involves elementary processes that are not "invertible," a deep insight into the irreversibility of natural processes. While incoming spherical waves of radiation are mathematically possible, they are not practically achievable. Nature appears to be asymmetric in time. He speculates that the continuous electromagnetic field might be made up of large numbers of light quanta - singular points in a field that superimpose collectively to create the wavelike behavior.

Although he could not formulate a mathematical theory that does justice to both the continuous oscillatory waves and the discrete particle pictures, Einstein argued that they could be "fused" and made compatible. This was over a decade before Erwin Schrödinger's wave mechanics and Werner Heisenberg's quantum mechanics. And because gases behave statistically, he knows that the connection between the wave and particles may involve probabilistic behavior.

When light was shown to exhibit interference and diffraction, it seemed almost certain that light should be considered a wave. The greatest advance in theoretical optics since the introduction of the oscillation theory was Maxwell's brilliant discovery that light can be understood as an electromagnetic process...One became used to treating electric and magnetic fields as fundamental concepts that did not require a mechanical interpretation. This path leads to the so-called relativity theory. I only wish to bring in one of its consequences, for it brings with it certain modifications of the fundamental ideas of physics. It turns out that the inertial mass of an object decreases by L / c2 when that object emits radiation of energy L...the inertial mass of an object is diminished by the emission of light.

The Emission and Absorption of Radiation (1916)

When he finished the years needed to complete his general theory of relativity, Einstein turned back to quantum theory and to Bohr's 1913 postulates about electrons jumping between stationary (non-radiating) states and radiating energy Em - En = hν. Where Bohr's two postulates provided amazingly accurate explanations of the Balmer and Lyman lines in the hydrogen spectrum, Einstein showed how to derive those postulates along with his latest, and so far simplest, derivation of the Planck radiation law.

Where Bohr and Planck had manipulated mathematical expressions to correspond with spectroscopic data, Einstein found the statistical probabilities for absorption and emission of light quanta when an electron jumps between discrete energy states, showing his deep physical understanding of interactions between electrons and radiation, going back over ten years. He predicted the existence of "stimulated emission" and showed quantum theory is the source of ontological chance.

At this time, Einstein felt very much alone in believing the reality (his emphasis) of light quanta:

I do not doubt anymore the reality of radiation quanta, although I still stand quite alone in this convictionEinstein derived "transition probabilities" for quantum jumps, described as A and B coefficients for the processes of absorption, spontaneous emission, and (his newly predicted) stimulated emission of radiation. In two papers, "Emission and Absorption of Radiation in Quantum Theory," and "On the Quantum Theory of Radiation," he again derived the Planck law (for Planck it was mostly a guess at the formula needed to fit spectroscopic observations), he derived Planck's postulate E = hν, and he derived Bohr's second postulate Em - En = hν. Einstein did this by exploiting the obvious relationship between the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution of gas particle velocities and the distribution of radiation in Planck's law. The formal similarity between the chromatic distribution curve for thermal radiation and the Maxwell velocity-distribution law is too striking to have remained hidden for long. In fact, it was this similarity which led W. Wien, some time ago, to an extension of the radiation formula in his important theoretical paper, in which he derived his displacement law...Not long ago I discovered a derivation of Planck's formula which was closely related to Wien's original argument and which was based on the fundamental assumption of quantum theory. This derivation displays the relationship between Maxwell's curve and the chromatic distribution curve and deserves attention not only because of its simplicity, but especially because it seems to throw some light on the mechanism of emission and absorption of radiation by matter, a process which is still obscure to us.But the introduction of Maxwell-Boltzmann statistical mechanical thinking to electromagnetic theory has produced what Einstein called a "weakness in the theory." It introduces the reality of an irreducible objective chance! If light quanta are particles with energy E = hν traveling at the velocity of light c, then they should have a momentum p = E/c = hν/c. When light is absorbed by material particles, this momentum will clearly be transferred to the particle. But when light is emitted by an atom or molecule, a problem appears.

The "statistical interpretation" of Max Born tells us the outgoing wave is the probability amplitude wave function Ψ, whose absolute square is the probability of finding a light particle in an arbitrary direction, as Einstein qualitatively knew well but never published.

Conservation of momentum requires that the momentum of the emitted particle will cause an atom to recoil with momentum hν/c in the opposite direction. However, the standard theory of spontaneous emission of radiation is that it produces a spherical wave going out in all directions. A spherically symmetric wave has no preferred direction. In which direction does the atom recoil? Einstein asked:

Does the molecule receive an impulse when it absorbs or emits the energy ε? For example, let us look at emission from the point of view of classical electrodynamics. When a body emits the radiation ε it suffers a recoil (momentum) ε/c if the entire amount of radiation energy is emitted in the same direction. If, however, the emission is a spatially symmetric process, e.g., a spherical wave, no recoil at all occurs. This alternative also plays a role in the quantum theory of radiation. When a molecule absorbs or emits the energy ε in the form of radiation during the transition between quantum theoretically possible states, then this elementary process can be viewed either as a completely or partially directed one in space, or also as a symmetrical (nondirected) one. It turns out that we arrive at a theory that is free of contradictions, only if we interpret those elementary processes as completely directed processes.But the inability to predict both the time and direction of light particle emissions, said Einstein in 1917, is "a weakness in the theory..., that it leaves time and direction of elementary processes to chance (Zufall, ibid.)." It is only a weakness for Einstein, of course, because his God does not play dice. Einstein clearly saw, as none of his contemporaries did, that since spontaneous emission is a statistical process, it cannot possibly be described with classical physics.One can give good reasons why reality cannot at all be represented by a continuous field. From the quantum phenomena it appears to follow with certainty that a finite system of finite energy can be completely described by a finite set of numbers (quantum numbers). This does not seem to be in accordance with a continuum theory, and must lead to an attempt to find a purely algebraic theory for the description of reality. But nobody knows how to obtain the basis of such a theory.It speaks in favor of the theory that the statistical law assumed for [spontaneous] emission is nothing but the Rutherford law of radioactive decay. The properties of elementary processes required...make it seem almost inevitable to formulate a truly quantized theory of radiation.Einstein may not have liked this conceptual crisis, but his insights into the indeterminism involved in quantizing matter and energy were known, if largely ignored, for another decade until Heisenberg's quantum theory introduced his famous uncertainty principle in 1927. Heisenberg states that the exact position and momentum of an atomic particle can only be known within certain (sic) limits. The product of the position error and the momentum error is greater than or equal to Planck's constant h/2π.

ΔpΔx ≥ h/2π

The Interaction of Radiation and Matter as the Origin of Irreversibility (1916)

In his two papers on quantum mechanics in 1916-17, Einstein's discovery of ontological chance is the most important contribution to physics and philosophy. But his insight into the asymmetry of the emission and absorption processes may be used to discover the origin of irreversibility and an explanation for Boltzmann's hypothesis of "molecular disorder."

What we might call Einstein's "radiation asymmetry" was introduced with these words,

When a molecule absorbs or emits the energy ε in the form of radiation during the transition between quantum theoretically possible states, then this elementary process can be viewed either as a completely or partially directed one in space, or also as a symmetrical (nondirected) one. It turns out that we arrive at a theory that is free of contradictions, only if we interpret those elementary processes as completely directed processes.The elementary process of the emission and absorption of radiation is asymmetric, because the process is directed, as Einstein had explicitly noted first in 1909, and we know he had seen as early as 1905. The apparent isotropy of the emission of radiation is only what Einstein called "pseudo-isotropy" (Pseudoisotropie), a consequence of time averages over large numbers of events. Einstein often substitutes time averages for space averages, or averages over the possible states of a system in statistical mechanics. a quantum theory free from contradictions can only be obtained if the emission process, just as absorption, is assumed to be directional. In that case, for each elementary emission process Zm->Zn a momentum of magnitude (εm—εn)/c is transferred to the molecule. If the latter is isotropic, we shall have to assume that all directions of emission are equally probable. If the molecule is not isotropic, we arrive at the same statement if the orientation changes with time in accordance with the laws of chance. Moreover, such an assumption will also have to be made about the statistical laws for absorption, (B) and (B'). Otherwise the constants Bmn and Bnm would have to depend on the direction, and this can be avoided by making the assumption of isotropy or pseudo-isotropy (using time averages).Now the principle of microscopic reversibility is a fundamental assumption of statistical mechanics. It underlies the principle of "detailed balancing," which is critical to the understanding of chemical reactions. In thermodynamic equilibrium, the number of forward reactions is exactly balanced by the number of reverse reactions. But microscopic reversibility, while true in the sense of averages over time, should not be confused with the reversibility of individual collisions between molecules. The equations of classical dynamics are reversible in time. And the deterministic Schrödinger equation of motion in quantum mechanics is also time reversible. Irreversibility thus depends on the "projection" of a superposition of states into a single state, the so-called "collapse" of the wave function.

The Quantum Statistics for Photons (1924)

In 1924, Einstein received an amazing very short paper from India by Satyendra Nath Bose. Einstein must have been pleased to read the title, "Planck's Law and the Hypothesis of Light Quanta." It was more attention to Einstein's 1905 work than anyone had paid in nearly twenty years. The paper began by claiming that the "phase space" (a combination of 3-dimensional coordinate space and 3-dimensional momentum space) should be divided into small volumes of h3, the cube of Planck's constant. By counting the number of possible distributions of light quanta over these cells, Bose claimed he could calculate the entropy and all other thermodynamic properties of the radiation.

Bose easily derived the inverse exponential function, Einstein too had derived this. Maxwell and Boltzmann derived it, without the additional -1, by analogy from the Gaussian exponential tail of probability and the theory of errors.

1 / (e - hν / kT -1)

(Planck had simply guessed this expression from Wien's law by adding the term - 1 in the denominator of Wien's a / e - bν / T).

All previous derivations of the Planck law, including Einstein's of 1916-17 (which Bose called "remarkably elegant"), used classical electromagnetic theory to derive the density of radiation, the number of "modes" or "degrees of freedom" of the radiation field,

ρνdν = (8πν2dν / c3) E

But now Bose showed he could get this quantity with a simple statistical mechanical argument remarkably like that Maxwell used to derive his distribution of molecular velocities. Where Maxwell said that the three directions of velocities for particles are independent of one another, but of course equal to the total momentum,

px2 + py2 + pz2 = p2 ,

Bose just used Einstein's relation for the momentum of a photon,

p = hν / c,

and he wrote

px2 + py2 + pz2 = h2ν2 / c2 .

This led him to calculate a frequency interval in phase space as

∫ dx dy dz dpx dpy dpz = 4πV ( hν / c )3 ( h dν / c ) = 4π ( h3 ν2 / c3 ) V dν,

which he simply divided by h3, multiplied by 2 to account for two polarization degrees of freedom, and he had derived the number of cells belonging to dν,

ρνdν = (8πν2dν / c3) E ,

without using classical radiation laws, a correspondence principle, or even Wien's law. His derivation was purely statistical mechanical, based only on the number of cells in phase space and the number of ways N photons can be distributed among them.

Einstein immediately translated the Bose paper into German and had it published in Zeitschrift für Physik, without even telling Bose. More importantly, Einstein then went on to discuss a new quantum statistics that predicted low-temperature condensation of any particles with integer values of the spin. So called Bose-Einstein statistics were quickly shown by Dirac to lead to the quantum statistics of half-integer spin particles called Fermi-Dirac statistics. Fermions are half-integer spin particles that obey Pauli's exclusion principle so a maximum of two particles, with opposite spins, can be found in the fundamental h3 volume of phase space identified by Bose.

Einstein's 1916 work on transition probabilities predicted the stimulated emission of radiation that brought us lasers (light amplification by the stimulated emission of radiation). Now his work on quantum statistics brought us the Bose-Einstein condensation. Either work would have made their discoverer a giant in physics, but these are more often attributed to Bose, just as Einstein's quantum discoveries before the Copenhagen Interpretation are mostly forgotten by historians and today's textbooks, or attributed to others.

This may have been Einstein's last positive contribution to quantum physics. Some judge his next efforts as purely negative attempts to discredit quantum mechanics, by graphically illustrating quantum phenomena that seem logically impossible or at least in violation of fundamental theories like his relativity. But information philosophy hopes to provide explanations for Einstein's paradoxes that depend on the immaterial nature of information.

The phenomena of nonlocality, nonseparability, and entanglement may not be made intuitive by our explanations, but they can be made understandable. And they can be visualized in a way that Einstein and Schrödinger might have liked, even if they might still have found the phenomena difficult to believe. We hope even the layperson will see our animations as providing them an understanding of what quantum mechanics is doing in the microscopic world. The animations present standard quantum physics as Einstein saw it, though Schrödinger never accepted the "collapse" of the wave function and the existence of particles making quantum jumps.

The Fifth Solvay Conference, On Electrons and Photons (1927)

Sadly, despite Einstein's two decades of pioneering work on the interaction of photons and electrons, his ideas and concerns were given little attention at this Solvay, though the conference was dedicated to electrons and photons.

The conference was dominated by papers on the new quantum theory delivered by Louis de Broglie, Niels Bohr, Max Born and Werner Heisenberg. It is best known for Einstein's after-hours suggestions to Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg probing for faults in the uncertainty principle. Accounts of these events have been told largely by the victors (there are no holes in uncertainty) but Einstein has said they often missed or ignored his important point. That point was the nonlocal behavior of a spherical light wave as it collapses to get absorbed by a single electron. This was Einstein's only contribution mentioned in the published proceedings.

Here are the notes on Einstein's original remarks at the conference and Bohr's brief response. They contain much of Einstein's 1935 EPR paper, except in 1927 only one particle is involved. Entanglement in EPR requires two identical particles.

Notice how Einstein's diagram clearly shows his concerns of over two decades about reconciling a spherical wave (his example is now an electron) and its collapse to being measured at just one point as if it is a particle. At this point in the history of quantum mechanics, wave-particle duality is seen as the debate between Schrödinger's wave mechanics and Heisenberg's particle mechanics.

Bohr's reaction to Einstein's presentation has been preserved. He didn't understand a word! He disingenuously claims he does not know what quantum mechanics is. His response is vague and ends with his ideas on complementarity and the inability to describe a causal spacetime reality. Twenty-two years later, in his contribution to the Schilpp memorial volume on Einstein, Bohr had no better response to Einstein's 1927 concerns. But he does remember vividly and provides a picture of what Einstein drew on the blackboard. Here is Bohr's 1949 recollection:

At the general discussion in Como, we all missed the presence of Einstein, but soon after, in October 1927, I had the opportunity to meet him in Brussels at the Fifth Physical Conference of the Solvay Institute, which was devoted to the theme "Electrons and Photons."Although Bohr seems to have missed Einstein's point completely, Werner Heisenberg at least came to explain it well. In his 1930 lectures at the University of Chicago, Heisenberg presented a critique of both particle and wave pictures, including a new example of nonlocality that Einstein had apparently developed since 1927. It includes Einstein's concern about "action-at-a-distance" that might violate his principle of relativity, and anticipates the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox. Heisenberg wrote: In relation to these considerations, one other idealized experiment (due to Einstein) may be considered. We imagine a photon which is represented by a wave packet built up out of Maxwell waves. It will thus have a certain spatial extension and also a certain range of frequency. By reflection at a semi-transparent mirror, it is possible to decompose it into two parts, a reflected and a transmitted packet. There is then a definite probability for finding the photon either in one part or in the other part of the divided wave packet. After a sufficient time the two parts will be separated by any distance desired; now if an experiment yields the result that the photon is, say, in the reflected part of the packet, then the probability of finding the photon in the other part of the packet immediately becomes zero. The experiment at the position of the reflected packet thus exerts a kind of action (reduction of the wave packet) at the distant point occupied by the transmitted packet, and one sees that this action is propagated with a velocity greater than that of light. However, it is also obvious that this kind of action can never be utilized for the transmission of signals so that it is not in conflict with the postulates of the theory of relativity.

Einstein visualizes Two-Particle Nonlocality (1933)

In 1933, shortly before he left Germany to emigrate to America,

Einstein attended a lecture on quantum electrodynamics by Leon

Rosenfeld. Keep in mind that Rosenfeld was perhaps the most

dogged defender of the Copenhagen Interpretation. After the talk,

Einstein asked Rosenfeld,

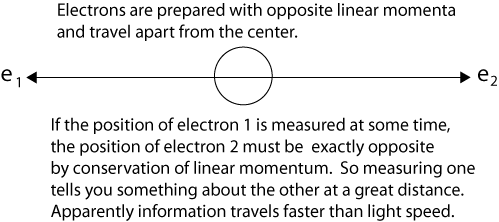

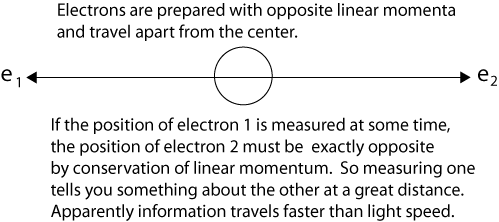

“What do you think of this situation?” Suppose two particles are set in motion towards each other with the same, very large, momentum, and they interact with each other for a very short time when they pass at known positions. Consider now an observer who gets hold of one of the particles, far away from the region of interaction, and measures its momentum: then, from the conditions of the experiment, he will obviously be able to deduce the momentum of the other particle. If, however, he chooses to measure the position of the first particle, he will be able tell where the other particle is. It is most unfortunate that Einstein did not explain that measuring the momentum of the first particle allows us to deduce the momentum of the second particle because of the conservation of linear momentum. The same conservation principle explains as Einstein says, "If, however, he chooses to measure the position of the first particle, he will be able tell where the other particle is." If Einstein had called this ability to tell "knowledge (information) at a distance," instead of "spooky action at a distance," entanglement might never have been thought "spooky" at all, just a correlation of properties. We can diagram a simple case of Einstein’s question as follows after the particles have interacted and separate from the center. We use electrons instead of generic particles, an anachronism introduced by David Bohm in 1952.

Recall that it was Einstein who discovered in 1924 the identical nature, indistinguishability, and interchangeability of some quantum particles. He found that identical particles are not independent, altering their quantum statistics.

After the particles interact at t1, quantum mechanics describes them with a single two-particle wave function that is not the product of independent single-particle wave functions. In the case of electrons, which are indistinguishable interchangeable particles, it is not proper to say electron 1 goes this way and electron 2 that way. (Nevertheless, it is convenient to label the particles, as we do in the illustration.)

Einstein then asked Rosenfeld, “How can the final state of the second

particle be influenced by a measurement performed on the first

after all interaction has ceased between them?” This was the germ

of the EPR paradox, and ultimately the problem of two-particle

entanglement.

Why does Einstein question Rosenfeld and describe this as an

“influence,” suggesting an “action-at-a-distance?”

It is only paradoxical in the context of Rosenfeld’s Copenhagen

Interpretation, since the second particle is not itself measured and

yet we know something about its properties, which the Copenhagen Interpretation

says we cannot know without an explicit measurement..

Einstein was clearly correct to tell Rosenfeld that at a later time t2, a measurement of one particle's position would instantly establish the position of the other particle - without measuring it. Einstein simply used conservation of linear momentum implicitly to calculate (and know) the position of the second particle.

Two years later, reacting to EPR, Schrödinger described two such particles as becoming "entangled" (verschränkt) at their first interaction, so "nonlocal" phenomena are also known as "quantum entanglement."

Although conservation laws are rarely cited as the explanation, they are the physical reason that entangled particles always produce correlated results for all properties. If the results were not always correlated, the implied violation of a fundamental conservation law would cause a much bigger controversy than entanglement itself, as puzzling as that is.

Note the anachronism of electrons as Einstein's generic particles. It was David Bohm in 1952 who proposed that Einstein's EPR problem use electrons. Today many if not most accounts of the EPR paradox describe it with electrons.

Einstein Accepts Quantum Mechanics But Still Hopes For A Continuum Theory (1934)

In 1934, Einstein described one way to reconcile nonlocality with a four-dimensional spacetime continuum theory. At this time, Einstein is clearly supportive of Heisenberg's uncertainty principle and the probabilistic nature of quantum theory:

Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen and Entanglement (1935)

Einstein and colleagues Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen, proposed in 1935 a paradox (known by their initials as EPR or as the Einstein-Podolsy-Rosen paradox) to exhibit internal contradictions in the new quantum physics. They hoped to show that quantum theory could not describe certain intuitive "elements of reality" and thus was incomplete. They said that, as far as it goes, quantum mechanics is correct, just not "complete."

Einstein was correct that quantum theory is "incomplete" relative to classical physics, which has twice as many dynamical variables that can be known with arbitrary precision. But half of this information is missing in quantum physics, due to the indeterminacy principle which allows only one of each pair of non-commuting observables (for example momentum or position) to be known with arbitrary accuracy. Even more important, an individual particle, cannot be said to have a known position before a measurement, since evolution described by the unitary and deterministic Schrödinger equation provides us only probabilities.

The most that can be said is that the particle can be found anywhere the probability amplitude is non-zero. This was the core idea of Einstein's claim of "incompleteness." For Bohr to deny this and call quantum mechanics "complete" was just to play word games, which infuriated Einstein.

Einstein was also correct that indeterminacy makes quantum theory an irreducibly discontinuous and statistical theory. Its predictions and highly accurate experimental results are statistical in that they depend on an ensemble of identical experiments, not on any individual experiment. Einstein wanted physics to be a continuous field theory, in which all physical variables are completely and locally determined by the four-dimensional field of space-time in his theory of relativity.

Einstein and his colleagues Erwin Schrödinger, Max Planck, (later David Bohm), and others hoped for a return to deterministic physics, and the elimination of mysterious quantum phenomena like the superposition of states, the mysterious "collapse" of the wave function, and Schrödinger's famous cat. EPR continues to fascinate determinist philosophers of science who hope to prove that quantum indeterminacy does not exist.

What happens according to the information interpretation of quantum mechanics is an instantaneous change in the information about probabilities (actually complex probability amplitudes). Nothing physical (matter or energy) is moving anywhere.

But Einstein was also bothered by what is known as "nonlocality," as we saw at the 1927 Solvay conference. This mysterious phenomenon was even more clearly exhibited in EPR experiments as the apparent transfer of something physical faster than the speed of light. Einstein may have already seen this inconsistency with his relativity theory in his 1905 papers.

The 1935 EPR paper was based on a question of Einstein's about two electrons fired in opposite directions from a central source with equal velocities. He imagined them starting at t0 some distance apart and approaching one another with high velocities. Then for a short time interval from t1 to t1 + Δt the particles are in contact with one another.

Most accounts of entanglement and nonlocality begin with the idea that distinguishable particles separate - particle 1 goes one way and particle 2 the other. But indistinguishable particles cannot be separated. And neither one has a distinct path between measurements.

After the particles are measured and become entangled at t1, quantum mechanics describes them with a single two-particle wave function that is not the product of two one-particle wave functions. Because electrons are indistinguishable particles, it is not proper to say electron 1 goes this way and electron 2 that way. (Nevertheless, it is convenient to label the particles, as we do in illustrations below.) It is misleading to think that specific particles have distinguishable paths.

Einstein said correctly that at a later time t2, a measurement of one electron's position would instantly establish the position of the other electron - without measuring it explicitly. And this is correct, just as after the collision of two billiard balls, measurement of one ball tells us exactly where the other one is due to conservation of momentum. But this is not "action at a distance." It is more nearly "knowledge at a distance."

Note that Einstein used conservation of linear momentum to calculate the position of the second electron. Although conservation laws are rarely cited as the explanation, they are the physical reason that entangled particles always produce correlated results. If the results were not always correlated, the implied violation of a fundamental conservation law would be a much bigger story than mysterious entanglement itself, as interesting as that is.

Visualizing Entanglement, Nonlocality, and Nonseparability

Schrödinger said that his "Wave Mechanics" provided more "visualizability" (Anschaulichkeit) than the "damned quantum jumps" of the Copenhagen school, as he called them. He was right. We can use the wave function to visualize EPR.

But we must focus on the probability amplitude wave function of the prepared two-particle state. We must not attempt to describe the paths or locations of independent particles - at least until after some measurement has been made. We must also keep in mind the conservation laws that Einstein used to describe nonlocal behavior in the first place. Then we can see that the "mystery" of nonlocality for two particles is primarily the same mystery as the single-particle collapse of the wave function. But there is an extra mystery, one we might call an "enigma," that results from the nonseparability of identical indistinguishable particles.

As Richard Feynman said, there is only one mystery in quantum mechanics (the superposition of states, the probabilities of collapse into one state, and the consequent statistical outcomes). The only difference in two-particle entanglement and nonlocality is that two particles appear simultaneously (in their original interaction frame) when their wave function collapses.

We choose to examine a phenomenon which is impossible, absolutely impossible, to explain in any classical way, and which has in it the heart of quantum mechanics. In reality, it contains the only mystery. We cannot make the mystery go away by "explaining" how it works. We will just tell you how it works. In telling you how it works we will have told you about the basic peculiarities of all quantum mechanics.In the time evolution of an entangled two-particle state according to the Schrödinger equation, we can visualize it - as we visualize the single-particle wave function - as collapsing when a measurement is made. The discontinuous "jump" is also described as the "reduction of the wave packet." This is apt in the two-particle case, where the superposition of | + - > and | - + > states is "projected" or "reduced" to one of these states, and then further reduced to the product of independent one-particle states. In the two-particle case (instead of just one particle making an appearance), when either particle is measured we know instantly those now determinate properties of the other particle that satisfy the conservation laws, including its location equidistant from, but on the opposite side of, the source.

Animation of a two-particle wave function collapsing - click to restart

"I consider [entanglement] not as one, but as the characteristic trait of quantum mechanics, the one that enforces its entire departure from classical lines of thought."Schrödinger knew that his two-particle wave function could not have the same simple interpretation as the single particle, which can be visualized in ordinary 3-dimensional configuration space. And he is right that entanglement exhibits a richer form of the "action-at-a-distance" and nonlocality that Einstein had already identified in the collapse of the single particle wave function. But the main difference is that two particles acquire new properties instead of one, and they do it instantaneously (at faster than light speeds), just as in the case of a single-particle measurement, where the finite probability of appearing at various distant locations collapses to zero at the instant the particle is found somewhere. We can enhance our visualization of what might be happening between the time two entangled electrons are emitted with opposite spins and the time one or both electrons are detected. Quantum mechanics describes the state of the two electrons as in a linear combination of | + - > and | - + > states. We can visualize the electron moving left to be both spin up | + > and spin down | - >. And the electron moving right would be both spin down | - > and spin up | + >. We could require that when the left electron is spin up | + >, the right electron must be spin down | - >, so that total spin is always conserved. Consider this possible animation of the experiment, which illustrates the assumption that each electron is in a linear combination of up and down spin. It imitates the superposition (or linear combination) with up and down arrows on each electron oscillating quickly. Notice that if you move the animation frame by frame by dragging the dot in the timeline, you will see that total spin = 0 is conserved. When one electron is spin up the other is always spin down. Since quantum mechanics says we cannot know the spin until it is measured, our best estimate is a 50/50 probability between up and down. This is the same as assuming Schrödinger's Cat is 50/50 alive and dead. But what this means of course is simply that if we do a large number of identical experiments, the statistics for live and dead cats will be approximately 50/50%. We never observe/measure a cat that is both dead and alive! As Einstein noted, QM tells us nothing about individual cats. Quantum mechanics is incomplete in this respect. He is correct, although Bohr and Heisenberg insisted QM is complete, because we cannot know more before we measure, and reality is created (they say) when we do measure. Despite accepting that a particular value of an "observable" can only be known by a measurement (knowledge is an epistemological problem, Einstein asked whether the particle actually (really, ontologically) has a path and position before we measure it? His answer was yes. Here is an animation that illustrates the unprovable assumption that the two electrons are randomly produced in a spin-up and a spin-down state, and that they remain in those states no matter how far they separate, provided neither interacts until the measurement. An interaction does what is described as decohering the two states.

How Mysterious Is Entanglement?

Some commentators say that nonlocality and entanglement are a "second revolution" in quantum mechanics, "the greatest mystery in physics," or "science's strangest phenomenon," and that quantum physics has been "reborn." They usually quote Erwin Schrödinger as saying

"I consider [entanglement] not as one, but as the characteristic trait of quantum mechanics, the one that enforces its entire departure from classical lines of thought."Schrödinger knew that his two-particle wave function could not have the same simple interpretation as the single particle, which can be visualized in ordinary 3-dimensional configuration space. And he is right that entanglement exhibits a richer form of the "action-at-a-distance" and nonlocality that Einstein had already identified in the collapse of the single particle wave function. But the main difference is that two particles acquire new properties instead of one, and they do it instantaneously (at faster than light speeds), just as in the case of a single-particle measurement. Nonlocality and entanglement are thus just another manifestation of Richard Feynman's "only" mystery. In both single-particle and two-particle cases paradoxes appear only when we attempt to describe independent particles following a path to measurement by observer A (and/or observer B).

Can a Special Frame Resolve the EPR Paradox?

Is it remotely possible that Einstein deliberately added an asymmetry to a problem that he knew is symmetric, in order to get physicists thinking more seriously about the questions he had been raising for decades, with no one ever taking them. or him, seriously?

Almost every presentation of the EPR paradox begins with something like "Alice observes one particle..." and concludes with the question "How does the second particle get the information needed so that Bob's measurements correlate perfectly with Alice?"

There is a fundamental asymmetry in this framing of the EPR experiment. It is a surprise that Einstein, who was so good at seeing deep symmetries, did not consider how to remove the asymmetry.

Consider this reframing: Alice's measurement collapses the two-particle wave function. The two indistinguishable particles simultaneously appear at locations in a space-like separation. The frame of reference in which the source of the two entangled particles and the two experimenters are at rest is a special frame in the following sense.

As Einstein knew very well, there are frames of reference moving with respect to the laboratory frame of the two observers in which the time order of the events can be reversed. In some moving frames Alice measures first, but in others Bob measures first.

If there is a special frame of reference (not a preferred frame in the relativistic sense), surely it is the one in which the origin of the two entangled particles is at rest. Assuming that Alice and Bob are also at rest in this special frame and equidistant from the origin, we arrive at the simple picture in which any measurement that causes the two-particle wave function to collapse makes both particles appear simultaneously at determinate places with fully correlated properties (just those that are needed to conserve energy, momentum, angular momentum, and spin).

Why Did Einstein De-emphasize Symmetry and Conservation Principles?

The experiment with two entangled particles was introduced by Einstein in the 1935 EPR paradox paper in the context of conserving momentum. In David Bohm's entangled electrons with total spin zero, the Copenhagen assumption that each particle is in a random unknown combination of spin up and spin down, independent of the other particle, simply because we have not yet measured either particle, is wrong and the source of the “paradox.” Just as a particle has an unknown but definite position, those entangled particles have opposing spins, even if the spins are unknown individually, they are interdependent jointly.

Einstein lived only a few years after Bohm's version and never commented on it as far as we know. But might he have said, following his use of momentum conservation in 1935, and in his 1933 remarks to Leon Rosenfeld, the following. When two particles travel away from the central source, with initial total spin zero, if one is ever measured as spin up, the other must be found with spin down? The operative principle for Einstein here would be conservation of spin. To assume that their spins are independent is to consider the absurd outcome that spins could be found both up (or down), a violation of a conservation principle that is much more egregious than the amazing fact spins are always perfectly correlated in any measurements.

Why also did Einstein not say that the overall problem is symmetric. It thus makes no sense to say that one particle is measured first, the other second, if they are in a space-like separation. In some other moving reference frames it will be the other particle that is measured first. Is Einstein setting a trap for lesser thinkers?

Einstein's Dream of a Continuous Field Theory

Einstein's dream of a continuous and deterministic unified field theory as a "theory of everything" gets in the way of his accepting the nonlocal and nonseparable, indeterministic and asymmetric character of radiation interactions with matter in quantum theory.

Einstein’s main objection to the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics was its claim that a particle has no position, or indeed any other observable property, until the particle is measured. He famously told the philosopher Hilary Putnam “Look, I don’t believe that when I am not in my bedroom my bed spreads out all over the room, and whenever I open the door and come in it jumps into the corner.”

Despite his reputation as the major critic of quantum mechanics, Einstein came to accept its indeterminism and statistical nature. As we have seen, he had himself discovered these aspects of quantum mechanics. If it is merely constructed on data derived from experience, he said quantum mechanics can only be approximate.

Einstein always hoped to discover - or invent - a more fundamental theory, preferably a field theory like the work of Newton and Maxwell and his own relativity theories. He dreamed of a single theory that would unite the gravitational field, the electromagnetic field, the “spinor field,” and even what he called the “ghost field” or “guiding field” of quantum mechanics.

Such a theory would use partial differential equations that predict field values continuously for all space and time. That theory would be a free invention of the human mind. Pure thought, he said, could comprehend the real, as the ancients dreamed.

Einstein wanted a field theory based on absolute principles such as the constant velocity of light, the conservation laws for energy and momentum, Ehrenfest’s adiabatic principle, symmetry principles, or Boltzmann’s principle that the entropy of a system depends on the possible distributions of its components.

We can now see the elements of Einstein’s interpretation, because fields are not substantial, like particles. They are abstract immaterial information that predicts the behavior of a particle at a given point in space and time, should one be there!

Fields are information. Particles are information structures.

A gravitational field describes paths in curved space that moving particles follow. An electromagnetic field describes the forces felt by an electric charge at each point. The wave function Ψ of quantum mechanics - we can think of it as a possibility field - provides probabilities that a particle will be found at a given point.

In all three cases continuous immaterial information describes causal influences over discrete material objects.

Note that the local values of all these fields depend on the distribution of matter in the rest of space, the so-called “boundary conditions.” Curvature of space depends on the distribution of masses. Electric fields depend on the distribution of charges. And quantum possibility fields depend on whether there are one or two slits open in the famous and mysterious experiment.

The quantum possibility field, calculated from the deterministically evolving Schrödinger equation, is a property of space. Like all fields, it exists whether or not there is a particle present. It only depends on the particle through the particle's wavelength.

Experiments with one-slit and two-slits open, showing the possibilities field calculated from | ψ |2. The possibilities field for two slits open applies whichever slit the particle enters. It is a property of the boundary conditions for the space.Following Einstein's objective reality view that particles have paths even if they cannot be measured, we can now animate the above cases of one slit open or two. Note that with two slits open, the paths start from one slit or the other, distributing themselves randomly between the interference fringes.  We can now summarize Einstein’s thinking about field theories, resulting in a new interpretation of quantum mechanics.

We can now summarize Einstein’s thinking about field theories, resulting in a new interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Einstein's Thoughts About Quantum Mechanics

1. Individual particles have the usual classical properties, like position and momentum, plus uniquely quantum properties, like spin, but these properties can only be established statistically. The quantum theory gives us statistical information about an individual particle position, probable values of all possible properties. A particle like an electron is a compact information structure with a definite position and momentum, even if it is unknown.

2. The quantum wave functions are fields. Einstein called them ghost fields or guiding fields. The fields are not the particles. The fields have values in many places at the same time. Particles are at one place at a time. Quantum field values are complex numbers which allow interference effects, causing some places to have no particles. Fields are not localized. Einstein showed that a particle of matter or energy is always localized. Light quanta are emitted and absorbed only as units, for example when one ejects an electron in the photoelectric effect.

3. Because quantum physics does not give us precise information about a particle’s location, it is incomplete when compared to classical physics. Quantum mechanics is a statistical theory and contains only probable information about an individual particle.

4. The Copenhagen notion of complementarity, that a quantum object is both a particle and a wave, or sometimes one and sometimes the other, depending on the measurements performed, is confusing and simply wrong. A particle is always a particle and the wave behavior of its probability field is simply one of the particle’s properties, like its mass, charge, spin, etc.

5. While the probability wave field is abstract and immaterial information, it causally influences the matter or energy, just as the particle’s spin dramatically alters its statistical properties, in particular its allowed positions, as Einstein showed in his 1924 discovery of quantum statistics. These nonintuitive behaviors are simply impossible in classical physics.

6. Although Niels Bohr deserves credit for arranging atoms in the periodic table, the deep reasons for two particles in the first shell and eight in the second were only clear after Einstein discovered spin statistics in 1924, following a suggestion by S. N. Bose.

7. In the two-slit experiment, Einstein’s localized particle always goes through one slit or the other, but when the two slits are open the probability wave function, which influences where the particle can land, is different from the wave function when one slit is open. The possibilities field (a wave) is determined by the boundary conditions of the experiment, which are different when only one slit is open. The particle does not go through both slits. It does not “interfere with itself.” It is never in two places at the same time.

8. The experiment with two entangled particles was introduced by Einstein in the 1935 EPR paradox paper. The Copenhagen assumption that each particle is in a random unknown combination of spin up and spin down, independent of the other particle, simply because we have not yet measured either particle, is wrong and the source of the “paradox.” Just as a particle has an unknown but definite position, entangled particles have definite spins, even if they are unknown individually, they are interdependent jointly.

Here is an animation that illustrates the assumption that the two electrons are randomly produced in a spin-up and a spin-down state, and that they remain in those states no matter how far they separate, provided neither interacts until the measurement. Any interaction does what is described as decohering the two states.

When the particles travel away from the central source, with total spin zero, one is at all times spin up, the other is spin down. The operative principle for Einstein is conservation of spin. To assume that their spins are independent is to consider the absurd outcome that spins could be found both up (or down), a violation of a conservation principle that is much more egregious than the amazing fact spins are always perfectly correlated in any measurements.

9. Erwin Schródinger explained to Einstein in 1936 that two entangled particles share a single wave function that can not be separated into the product of two single-particle wave functions, at least not until there is an interaction with another system that decoheres their perfect correlation.

10. Einstein ultimately accepted the indeterminism in quantum mechanics and the uncertainty in conjugate variables, despite the clumsy attempt by his colleagues Podolsky and Rosen to challenge uncertainty and restore determinism in the EPR paper.

11. In 1931 Einstein called P.A.M.Dirac’s transformation theory “the most perfect exposition, logically, of this [quantum] theory” even though it lacks “enough information to enable one to decide” a particle’s exact properties. In 1933 Dirac reformulated quantum physics using a Lagrangian rather than the standard Hamiltonian representation. The time integral of the Lagrangian has the dimensions of action, the same as Planck’s quantum of action h. And the principle of least action visualizes the solution of dynamical equations like Hamilton’s as exploring all paths to find that path with minimum action.

Dirac’s work led Richard Feynman to invent the path-integral formulation of quantum mechanics. The transactional interpretations of John Cramer and Ruth Kastner have a similar view. The basic idea of exploring all paths is in many ways equivalent to saying that the probabilities of various paths are determined by a solution of the wave equation using the boundary conditions of the experiment. As we saw above, such solutions involve whether one or two slits are open, leading directly to the predicted interference patterns, given only the wavelength of the particle.

12. In the end, of course, Einstein held out for a continuous field theory, one that could not be established on the basis of any number of empirical facts about measuring particles, but must be based on the discovery of principles, logically simple mathematical conditions which determine the field with differential equations. His lifelong dream was a “unified field theory,” one that at least combined the gravitational field and electromagnetic field, and one that might provide an underpinning for quantum mechanics someday.

Einstein was clear that even if his unified field theory was to be deterministic and causal, the statistical indeterminism of quantum mechanics itself would have to be preserved.

This seemingly impossible requirement is easily met if we confine the determinism to Einstein’s continuous field theories, which are pure abstract immaterial information. Einstein’s discovery of indeterminism and the statistical nature of physics we apply only to particles, which are information structures, new information in the universe created by the rearrangement of matter, while subject to the second law of thermodynamics.

Summary of Einstein's Objections to Quantum Mechanics

Perhaps the major reason for historians of quantum mechanics (writing since the Copenhagen Interpretation) to largely ignore Einstein is that he was the single most important critic of the quantum mechanics formulated in the late 1920's by Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Max Born, Pascual Jordan, Wolfgang Pauli, and Paul DIrac, whose work became the "standard orthodox" interpretation of quantum mechanics. So Einstein today is remembered more for his later attacks than for his truly extraordinary fundamental contributions to quantum theory before its so-called "founding.".

Einstein's major objection was that quantum mechanics is a statistical theory, one that predicts probable results for a large number of experiments, but nothing about specific events, like the exact time of a radioactive decay or the direction of spontaneous emission of a photon. This "chance" behavior of individual systems was something that Einstein himself had pointed out in his early papers. But without the ability to predict individual events with certainty, he maintained that quantum mechanics must remain an incomplete theory.

Quantum mechanics can precisely specify fewer physical variables than classical mechanics. Because of the indeterminacy principle, only one of each pair of non-commuting observables (momentum or position, for example) can be specified precisely. In this sense, classical theory is more complete. It contains more information. But rather than simply accept Einstein's description and terminology, Bohr, Heisenberg and others engaged in linguistic debates, claiming that quantum theory is itself "complete." They simply denied that more could be known about an underlying reality.

A second concern for Einstein was that the wave function ψ for an isolated free particle evolves in time to occupy all space. All positions become equally probable. Yet when we observe the particle, it is always located at some particular place. This does not prove that the particle had a particular place before the observation, but Einstein had a commitment to "elements of reality" that he thought no one could doubt. One of those elements is a particle's position. He asked the question, "Does the particle have a precise position the moment before it is measured?" The Copenhagen answer was sometimes "no," more often it was "we don't know."

If there is only one possible prior position for the particle, its path in four-dimensional space-time is fixed and determinate independently of the time. Complete path information is constant for all time. Quantum theory, by contrast, allows alternative possibilities (with calculable probabilities) that are critical if there is to be more than one possible future.

A third (and related) problem for Einstein was the appearance of "nonlocal" behavior, in the "collapse" of the wave function, in the two-slit experiment, and in the EPR experiment "entangling" two particles. Einstein thought in 1927 at the Solvay conference that nonlocality violated his theory of special relativity.

He drew a diagram on the blackboard illustrating the problem for a single particle. When the particle appears at point P on the right, what becomes of the wave that was going off to the left? Its "collapse" appears to violate his relativity principle. All the modern collapse-deniers (Bohm, Everett, Zeh, Zurek) are following Einstein and Schrödinger, thinking that the wave function might be something tangible and real.

Beyond nonlocality, but closely connected, a fourth problem was the nonseparability of indistinguishable particles. It was the centerpiece of his 1935 criticisms of quantum theory. Already in 1927 Einstein expressed concerns about wave functions that describe two particles. He said that two configurations of a system that are distinguished only by the permutation of two particles of the same species are represented by two different points (in configuration space), which is not in accord with his new results in quantum gas statistics.