|

Philosophers

Mortimer Adler Rogers Albritton Alexander of Aphrodisias Samuel Alexander William Alston Anaximander G.E.M.Anscombe Anselm Louise Antony Thomas Aquinas Aristotle David Armstrong Harald Atmanspacher Robert Audi Augustine J.L.Austin A.J.Ayer Alexander Bain Mark Balaguer Jeffrey Barrett William Barrett William Belsham Henri Bergson George Berkeley Isaiah Berlin Richard J. Bernstein Bernard Berofsky Robert Bishop Max Black Susanne Bobzien Emil du Bois-Reymond Hilary Bok Laurence BonJour George Boole Émile Boutroux Daniel Boyd F.H.Bradley C.D.Broad Michael Burke Jeremy Butterfield Lawrence Cahoone C.A.Campbell Joseph Keim Campbell Rudolf Carnap Carneades Nancy Cartwright Gregg Caruso Ernst Cassirer David Chalmers Roderick Chisholm Chrysippus Cicero Tom Clark Randolph Clarke Samuel Clarke Anthony Collins Antonella Corradini Diodorus Cronus Jonathan Dancy Donald Davidson Mario De Caro Democritus Daniel Dennett Jacques Derrida René Descartes Richard Double Fred Dretske John Earman Laura Waddell Ekstrom Epictetus Epicurus Austin Farrer Herbert Feigl Arthur Fine John Martin Fischer Frederic Fitch Owen Flanagan Luciano Floridi Philippa Foot Alfred Fouilleé Harry Frankfurt Richard L. Franklin Bas van Fraassen Michael Frede Gottlob Frege Peter Geach Edmund Gettier Carl Ginet Alvin Goldman Gorgias Nicholas St. John Green H.Paul Grice Ian Hacking Ishtiyaque Haji Stuart Hampshire W.F.R.Hardie Sam Harris William Hasker R.M.Hare Georg W.F. Hegel Martin Heidegger Heraclitus R.E.Hobart Thomas Hobbes David Hodgson Shadsworth Hodgson Baron d'Holbach Ted Honderich Pamela Huby David Hume Ferenc Huoranszki Frank Jackson William James Lord Kames Robert Kane Immanuel Kant Tomis Kapitan Walter Kaufmann Jaegwon Kim William King Hilary Kornblith Christine Korsgaard Saul Kripke Thomas Kuhn Andrea Lavazza James Ladyman Christoph Lehner Keith Lehrer Gottfried Leibniz Jules Lequyer Leucippus Michael Levin Joseph Levine George Henry Lewes C.I.Lewis David Lewis Peter Lipton C. Lloyd Morgan John Locke Michael Lockwood Arthur O. Lovejoy E. Jonathan Lowe John R. Lucas Lucretius Alasdair MacIntyre Ruth Barcan Marcus Tim Maudlin James Martineau Nicholas Maxwell Storrs McCall Hugh McCann Colin McGinn Michael McKenna Brian McLaughlin John McTaggart Paul E. Meehl Uwe Meixner Alfred Mele Trenton Merricks John Stuart Mill Dickinson Miller G.E.Moore Thomas Nagel Otto Neurath Friedrich Nietzsche John Norton P.H.Nowell-Smith Robert Nozick William of Ockham Timothy O'Connor Parmenides David F. Pears Charles Sanders Peirce Derk Pereboom Steven Pinker U.T.Place Plato Karl Popper Porphyry Huw Price H.A.Prichard Protagoras Hilary Putnam Willard van Orman Quine Frank Ramsey Ayn Rand Michael Rea Thomas Reid Charles Renouvier Nicholas Rescher C.W.Rietdijk Richard Rorty Josiah Royce Bertrand Russell Paul Russell Gilbert Ryle Jean-Paul Sartre Kenneth Sayre T.M.Scanlon Moritz Schlick John Duns Scotus Arthur Schopenhauer John Searle Wilfrid Sellars David Shiang Alan Sidelle Ted Sider Henry Sidgwick Walter Sinnott-Armstrong Peter Slezak J.J.C.Smart Saul Smilansky Michael Smith Baruch Spinoza L. Susan Stebbing Isabelle Stengers George F. Stout Galen Strawson Peter Strawson Eleonore Stump Francisco Suárez Richard Taylor Kevin Timpe Mark Twain Peter Unger Peter van Inwagen Manuel Vargas John Venn Kadri Vihvelin Voltaire G.H. von Wright David Foster Wallace R. Jay Wallace W.G.Ward Ted Warfield Roy Weatherford C.F. von Weizsäcker William Whewell Alfred North Whitehead David Widerker David Wiggins Bernard Williams Timothy Williamson Ludwig Wittgenstein Susan Wolf Scientists David Albert Michael Arbib Walter Baade Bernard Baars Jeffrey Bada Leslie Ballentine Marcello Barbieri Gregory Bateson Horace Barlow John S. Bell Mara Beller Charles Bennett Ludwig von Bertalanffy Susan Blackmore Margaret Boden David Bohm Niels Bohr Ludwig Boltzmann Emile Borel Max Born Satyendra Nath Bose Walther Bothe Jean Bricmont Hans Briegel Leon Brillouin Stephen Brush Henry Thomas Buckle S. H. Burbury Melvin Calvin Donald Campbell Sadi Carnot Anthony Cashmore Eric Chaisson Gregory Chaitin Jean-Pierre Changeux Rudolf Clausius Arthur Holly Compton John Conway Simon Conway-Morris Jerry Coyne John Cramer Francis Crick E. P. Culverwell Antonio Damasio Olivier Darrigol Charles Darwin Richard Dawkins Terrence Deacon Lüder Deecke Richard Dedekind Louis de Broglie Stanislas Dehaene Max Delbrück Abraham de Moivre Bernard d'Espagnat Paul Dirac Hans Driesch John Dupré John Eccles Arthur Stanley Eddington Gerald Edelman Paul Ehrenfest Manfred Eigen Albert Einstein George F. R. Ellis Hugh Everett, III Franz Exner Richard Feynman R. A. Fisher David Foster Joseph Fourier Philipp Frank Steven Frautschi Edward Fredkin Augustin-Jean Fresnel Benjamin Gal-Or Howard Gardner Lila Gatlin Michael Gazzaniga Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen GianCarlo Ghirardi J. Willard Gibbs James J. Gibson Nicolas Gisin Paul Glimcher Thomas Gold A. O. Gomes Brian Goodwin Joshua Greene Dirk ter Haar Jacques Hadamard Mark Hadley Patrick Haggard J. B. S. Haldane Stuart Hameroff Augustin Hamon Sam Harris Ralph Hartley Hyman Hartman Jeff Hawkins John-Dylan Haynes Donald Hebb Martin Heisenberg Werner Heisenberg Grete Hermann John Herschel Basil Hiley Art Hobson Jesper Hoffmeyer Don Howard John H. Jackson William Stanley Jevons Roman Jakobson E. T. Jaynes Pascual Jordan Eric Kandel Ruth E. Kastner Stuart Kauffman Martin J. Klein William R. Klemm Christof Koch Simon Kochen Hans Kornhuber Stephen Kosslyn Daniel Koshland Ladislav Kovàč Leopold Kronecker Rolf Landauer Alfred Landé Pierre-Simon Laplace Karl Lashley David Layzer Joseph LeDoux Gerald Lettvin Gilbert Lewis Benjamin Libet David Lindley Seth Lloyd Werner Loewenstein Hendrik Lorentz Josef Loschmidt Alfred Lotka Ernst Mach Donald MacKay Henry Margenau Owen Maroney David Marr Humberto Maturana James Clerk Maxwell Ernst Mayr John McCarthy Warren McCulloch N. David Mermin George Miller Stanley Miller Ulrich Mohrhoff Jacques Monod Vernon Mountcastle Emmy Noether Donald Norman Travis Norsen Alexander Oparin Abraham Pais Howard Pattee Wolfgang Pauli Massimo Pauri Wilder Penfield Roger Penrose Steven Pinker Colin Pittendrigh Walter Pitts Max Planck Susan Pockett Henri Poincaré Daniel Pollen Ilya Prigogine Hans Primas Zenon Pylyshyn Henry Quastler Adolphe Quételet Pasco Rakic Nicolas Rashevsky Lord Rayleigh Frederick Reif Jürgen Renn Giacomo Rizzolati A.A. Roback Emil Roduner Juan Roederer Jerome Rothstein David Ruelle David Rumelhart Robert Sapolsky Tilman Sauer Ferdinand de Saussure Jürgen Schmidhuber Erwin Schrödinger Aaron Schurger Sebastian Seung Thomas Sebeok Franco Selleri Claude Shannon Charles Sherrington Abner Shimony Herbert Simon Dean Keith Simonton Edmund Sinnott B. F. Skinner Lee Smolin Ray Solomonoff Roger Sperry John Stachel Henry Stapp Tom Stonier Antoine Suarez Leo Szilard Max Tegmark Teilhard de Chardin Libb Thims William Thomson (Kelvin) Richard Tolman Giulio Tononi Peter Tse Alan Turing C. S. Unnikrishnan Nico van Kampen Francisco Varela Vlatko Vedral Vladimir Vernadsky Mikhail Volkenstein Heinz von Foerster Richard von Mises John von Neumann Jakob von Uexküll C. H. Waddington James D. Watson John B. Watson Daniel Wegner Steven Weinberg Paul A. Weiss Herman Weyl John Wheeler Jeffrey Wicken Wilhelm Wien Norbert Wiener Eugene Wigner E. O. Wilson Günther Witzany Stephen Wolfram H. Dieter Zeh Semir Zeki Ernst Zermelo Wojciech Zurek Konrad Zuse Fritz Zwicky Presentations Biosemiotics Free Will Mental Causation James Symposium |

David Layzer

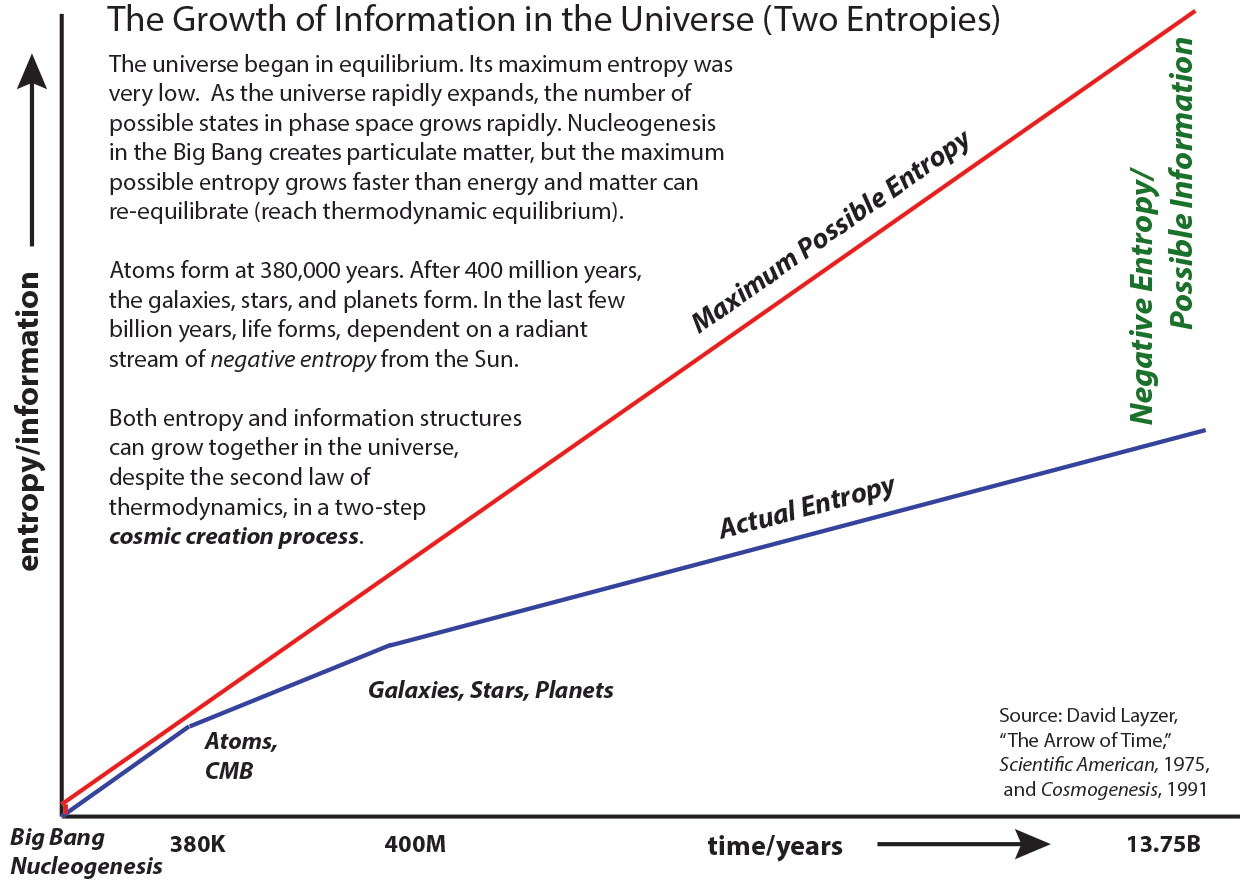

This illustration was created in 2006 based on Layzer's verbal description in his 1975 Scientific American article. It has been posted on this I-Phi website since that time.

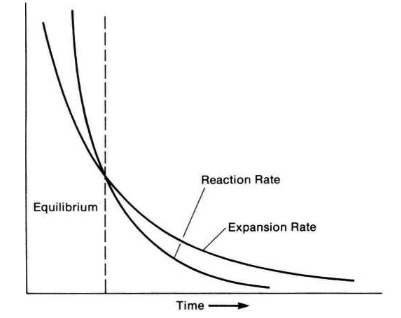

In his 1990 book Cosmogenesis, Layzer reiterated his model for the growth of order and drew a graph comparing the rates of universe expansion and equilibration rates. He wrote,

This illustration was created in 2006 based on Layzer's verbal description in his 1975 Scientific American article. It has been posted on this I-Phi website since that time.

In his 1990 book Cosmogenesis, Layzer reiterated his model for the growth of order and drew a graph comparing the rates of universe expansion and equilibration rates. He wrote,

It follows that the rates of equilibrium-maintaining reactions must have exceeded the rate of cosmic expansion early in the cosmic expansion. Eventually, however, the rate of any given equilibrium-maintaining reaction must become smaller than the rate of cosmic expansion, as illustrated in Figure 8.6. The curve representing the reaction rate is steeper than the curve representing the expansion rate.

If everything that happens was certain to happen, as determinist philosophers and scientists claim, no new information would ever enter the universe. Information would be a universal constant, like matter and energy. There would be "nothing new under the sun." Every past and future event could in principle be known (as Gottfried Leibniz and Pierre-Simon Laplace suggested) by a super-intelligence with access to such a fixed totality of information. It is of the deepest philosophical significance that information is based on the mathematics of probability. If all outcomes were certain, there would be no “surprises” in the universe. Information would be conserved and a universal constant, as some mathematical physicists mistakenly believe. Information philosophy requires the ontological uncertainty and probabilistic outcomes of modern quantum physics to produce new information. From Newton’s time to the start of the 19th century, the Laplacian view coincided with the notion of the divine foreknowledge of an omniscient God. On this view, complete, perfect and constant information exists at all times that describes the designed evolution of the universe and of the creatures inhabiting the world. In this God’s-eye view, information is a constant of nature. Some mathematicians argue that information must be a conserved quantity, like matter and energy. They are wrong. In Laplace's view, information would be a constant straight line over all time, as shown here.  If information were a universal constant, there would be “nothing new under the sun.” Every past and future event can in principle be known by Laplace's super-intelligent demon, with its access to such a fixed totality of information.

Since William Thomson (Lord Kelvin), James Clerk Maxwell, and Ludwig Boltzmann, most physicists and astronomers have believed that the universe began with a high degree of organization or order (or information) and that it has been running down ever since.

Hermann Helmholtz described this as the “heat death” of the universe.

If information were a universal constant, there would be “nothing new under the sun.” Every past and future event can in principle be known by Laplace's super-intelligent demon, with its access to such a fixed totality of information.

Since William Thomson (Lord Kelvin), James Clerk Maxwell, and Ludwig Boltzmann, most physicists and astronomers have believed that the universe began with a high degree of organization or order (or information) and that it has been running down ever since.

Hermann Helmholtz described this as the “heat death” of the universe.

Mathematicians who are convinced that information is always conserved argue that macroscopic order is disappearing into microscopic order, and that this hidden information could in principle be recovered, if time could only be reversed.

Kelvin’s claim that information must be destroyed when entropy increases would be correct if the universe were a closed system. But in our open and expanding universe, Layzer showed that the maximum possible entropy is increasing faster than the actual entropy. The difference between maximum possible entropy and the current entropy is called negative entropy, opening the possibility for complex and stable information structures to develop.

We can see from the "Growth of Order" figure that it is not only entropy that increases in the direction of the arrow of time, but also the information content of the universe. We can describe the new information as "emerging."

Layzer showed that the standard mathematician's view is wrong for our expanding universe.

Mathematicians who are convinced that information is always conserved argue that macroscopic order is disappearing into microscopic order, and that this hidden information could in principle be recovered, if time could only be reversed.

Kelvin’s claim that information must be destroyed when entropy increases would be correct if the universe were a closed system. But in our open and expanding universe, Layzer showed that the maximum possible entropy is increasing faster than the actual entropy. The difference between maximum possible entropy and the current entropy is called negative entropy, opening the possibility for complex and stable information structures to develop.

We can see from the "Growth of Order" figure that it is not only entropy that increases in the direction of the arrow of time, but also the information content of the universe. We can describe the new information as "emerging."

Layzer showed that the standard mathematician's view is wrong for our expanding universe.

Roger Penrose

In his 1989 book The Emperor's New Mind, Penrose speculated on the connection between information, entropy, and the arrow of time.

Recall that the primordial fireball was a thermal state — a hot gas in expanding thermal equilibrium. Recall, also, that the term 'thermal equilibrium' refers to a state of maximum entropy. (This was how we referred to the maximum entropy state of a gas in a box.) However, the second law demands that in its initial state, the entropy of our universe was at some sort of minimum, not a maximum! What has gone wrong? One 'standard' answer would run roughly as follows:Clearly, Penrose's "standard" answer is the work of David Layzer, likely based on a suggestion by Arthur Stanley Eddington. Penrose had met Layzer at a 1963 conference at Cornell University on the "Nature of Time" organized by Thomas Gold. It was at this conference that Layzer introduced his strong cosmological principle.True, the fireball was effectively in thermal equilibrium at the beginning, but the universe at that time was very tiny. The fireball represented the state of maximum entropy that could be permitted for a universe of that tiny size, but the entropy so permitted would have been minute by comparison with that which is allowed for a universe of the size that we find it to be today. As the universe expanded, the permitted maximum entropy increased with the universe's size, but the actual entropy in the universe lagged well behind this permitted maximum. The second law arises because the actual entropy is always striving to catch up with this permitted maximum. Arrows of Time

At the Cornell conference were Gold's British colleagues Hermann Bondi and Fred Hoyle. "Tommy" Gold was a brilliant cosmologist who proposed eliminating the puzzling "origin" of the universe by following earlier suggestions by James Jeans in 1928 and Paul Dirac in 1937.

Layzer identified what he called the "historical arrow of time," (the direction of increasing information), adding it to other arrows. The phrase "time's arrow" was coined by Eddington, who identified it with the direction of increasing entropy. It is now known as the "thermodynamic arrow of time."

In a 1975 article for Scientific American called The Arrow of Time, Layzer wrote:

the complexity of the astronomical universe seems puzzling.Layzer specifically identified this process as generating novelty and contradicting a deterministic view of the world, with significant implications for human freedom: Novelty and Determinism We have now traced the thermodynamic arrow and the historical arrow to their common source: the initial state of the universe. In that state microscopic information is absent and macroscopic information is either absent or minimal. The expansion from that state has generated entropy as well as macroscopic structure. Microscopic information, on the other hand, is absent from newly formed astronomical systems, and that is why they and their subsystems exhibit the thermodynamic arrow. This view of the world evolving in time differs radically from the one that has dominated physics and astronomy since the time of Newton, a view that finds its classic expression in the words of Pierre Simon de Laplace: "An intelligence that, at a given instant, was acquainted with all the forces by which nature is animated and with the state of the bodies of which it is composed, would - if it were vast enough to submit these data to analysis - embrace in the same formula the movements of the largest bodies in the Universe and those of the lightest atoms: nothing would be uncertain for such an intelligence, and the future like the past would be present to its eyes." In Laplace's world there is nothing that corresponds to the passage of time. For Laplace's "intelligence," as for the God of Plato, Galileo and Einstein, the past and the future coexist on equal terms, like the two rays into which an arbitrarily chosen point divides a straight line. If the theories I have presented here are correct, however, not even the ultimate computer - the universe itself - ever contains enough information to completely specify its own future states. The present moment always contains an element of genuine novelty and the future is never wholly predictable. Because biological processes also generate information and because consciousness enables us to experience those processes directly, the intuitive perception of the world as unfolding in time captures one of the most deep-seated properties of the universe.

Note that the deterministic Laplacian universe contains exactly the same information at all times - "nothing new under the sun."

In 1990, Layzer extended these ideas in his book Cosmogenesis: The Growth of Order in the Universe. He added a discussion of quantum mechanics and its implications for free will. First he noted a number of paradoxes, between microscopic quantum systems and the macroscopic universe, between standard thermodynamic macrophysics and cosmology, between irreducible randomness and human ignorance, and between the objective timeless being of the Laplacian view and the subjective human experience of becoming and change.

Conflicts and Paradoxes The relation between quantum physics, which describes the invisible world of elementary particles and their interactions, and macroscopic physics, which describes the world of ordinary experience, has perplexed physicists since the birth of quantum physics in 1925. Viewed as a system of mathematical laws, quantum physics includes macroscopic physics as a limiting case. By that I mean that quantum physics and macroscopic physics make the same predictions in the domain where macroscopic physics has been strongly corroborated (the macroscopic domain), but quantum physics also successfully describes the behavior and structure of molecules; atoms, and subatomic particles (the microscopic domain). Yet from another point of view, macroscopic physics seems more fundamental than quantum physics. As we will see later, the laws of quantum physics refer explicitly to the results of measurement. But every measurement necessarily has at least one foot in the world of ordinary experience: it has to be recorded in somebody's lab notebook or on magnetic tape. So quantum physics seems to presuppose its own limiting case — macroscopic physics. This is the mildest of several paradoxes that have sprung up in the region where quantum physics and macrophysics meet and overlap. The relation between macrophysics and cosmology is also problematic. The central law of macroscopic physics — the second law of thermodynamics — was understood by its inventors, and is still understood by most scientists, to imply that the Universe is running down — that order is degenerating into chaos. How can we reconcile such a tendency with the fact that the world is full of order — that it is a kosmos in both senses of the word. Some scientists say, "The contradiction is only apparent, The Second Law assures us that the Universe is running down, so it must have begun with a vast supply of order that is gradually being dissipated. But this way of trying to resolve the difficulty takes us from the frying pan into the fire, because, as we will see, modern cosmology strongly suggests that the early Universe contained far less order than the present-day Universe. Astronomical evolution and biological evolution are both stories of emerging order. Nevertheless, the views of time and change implicit in modern physics and modern biology are radically different. The physical sciences teach us that all natural phenomena are governed by mathematical laws that connect every physical event with earlier and later events. Imagine that every past and future event was recorded on an immense roll of film. If we knew all the physical laws, we could reconstruct the whole film from a single frame. And in principle there is nothing to prevent us from acquiring complete knowledge of a single frame. This worldview is epitomized in a much-quoted passage by one of Newton's most illustrious successors, the mathematician and theoretical astronomer Pierre Simon de Laplace (1749-1827):We ought then to regard the present state of the Universe as the effect of its previous state and the cause of the one that follows. An intelligence that at a given instant was acquainted with all the forces by which nature is animated and with the state of the bodies of which it is composed would — if it were vast enough to submit these data to analysis — embrace in the same formula the movements of the largest bodies in the Universe and those of the lightest atoms: Nothing would be uncertain for such an intelligence, and the future like the past would be present to its eyes. The human mind offers, in the perfection it has been able to give to astronomy, a feeble idea of this intelligence.Much the same view of the world was held by Albert Einstein:The scientist is possessed by the sense of universal causation. The future, to him, is every whit as necessary and determined as the past.Most contemporary physical scientists would probably agree with Laplace and Einstein. The world they study is a block universe, a four-dimensional net of causally connected events with time as the fourth dimension. In this world, no moment in time is singled out as "now." For Laplace's Intelligence, the future and the past don't exist in an absolute sense, as they do for us. How does life, regarded as a scientific phenomenon, fit into this worldview? A modern Laplacian might reply: Living organisms are collections of molecules that move and interact with one another and with their environment according to the same laws that govern molecules in nonliving matter. A supercomputer, supplied with a complete microscopic description of the biosphere and its environment, would be able to predict the future of life on Earth and to deduce its initial state. Implicit in the present state of the biosphere and its environment are the precise conditions that prevailed in the lifeless broth of organic molecules in which the first self-replicating molecules formed, And implicit in the conditions that prevailed in that broth and its environment is every detail of the living world of today. If you believe that living matter is subject to the same laws as nonliving matter and few, if any, contemporary biologists would dispute this assertion - this argument may seem compelling. Yet it clashes with two key aspects of the evolutionary process as described by contemporary evolutionary biologists: randomness and creativity. Randomness is an essential feature of the reproductive process. In nearly every biological population, new genes and new combinations of genes appear in every generation. Reproduction, whether sexual or asexual, involves the copying of genetic material (DNA). In all modern organisms the copying process is astonishingly accurate. But it isn't perfect. Occasionally there are copying errors, and these have a random character. In sexually reproducing populations there is another source of randomness: the genetic material of each individual is a random combination of contributions from each parent. The creative factor in biological evolution is natural selection, the tendency of genetic changes that favor survival and reproduction to spread in a population, and of changes that hinder survival and reproduction to die out. From the raw material provided by genetic variation, natural selection fashions new biological structures, functions, and behaviors. A mainstream physicist might reply that the apparent randomness of genetic variation is just a consequence of human ignorance — our inability to understand exceedingly complex but nevertheless completely determinate causal processes — and that evolution is "creative" only in a metaphorical sense. According to this view, evolution merely brings to light varieties of order prefigured in the prebiotic broth. There is an even more fundamental difference between the physical and the biological views of reality: the physicist's picture of reality seems impossible to reconcile with subjective experience. For there is nothing in the neo-Laplacian picture that corresponds to the central feature of human experience, the passage of time. We humans must watch the film unwind, but Laplace's Intelligence sees it whole. Nor is there anything that corresponds to the aspect of reality (as we experience it) that Greek philosophers called becoming, as opposed to the timeless being of numbers, triangles, and circles. The universe of modern physics is an enormously expanded and elaborated version of the perfectly ordered but static and lifeless world we encounter in Euclid's Elements, of which it is indeed a direct descendant. The biologist's world seems entirely different. Life, as we experience it, is inseparable from unpredictability and novelty.

Layzer then examines the role of chance in human freedom and finds that no one has been able to explain what even fundamental quantum mechanical randomness has to do with free choice and moral responsibility.

Freedom and Necessity What is the relation between being and becoming? Is the future as fixed and immutable as the past? What is chance? These questions bear on one of the perennial problems of Western philosophy, the problem of freedom and necessity. Each of us belongs to two distinct worlds. As objects in the world that natural science describes we are governed by universal laws. To Laplace's Intelligence we are systems of molecules whose movements are no less predicable and no more the results of free choice than the movements of the planets around the Sun. but as the subjects of our own experience we see the world differently; not as bundles of events frozen into the block universe of Laplace and Einstein like flies in amber, but as the authors of our own actions, the molders of our own lives. However strongly we may believe in the universality of physical laws, we cannot suppress the intuitive conviction that the future is to some degree open and that we help to shape it by our own free choices. This conviction lies at the basis of every ethical system. Without freedom there can be no responsibility. If we are not really free agents — if our felt freedom is illusory — how can we be guided in our behavior by ethical precepts? And why should society punish some acts and reward others? The Laplacian worldview tends to undermine the basis for ethical behavior. Judeo-Christian theology faces a similar problem. Although Laplace's Intelligence is not the Judeo-Christian God — Laplace's Intelligence observes and calculates; the Judeo-Christian God wills and acts ("Necessitie and chance approach not mee, and what I will is Fate," says the Almighty in Milton's Paradise Lost)— they contemplate similar universes. Nothing is uncertain for an all-knowing God, and the future, like the past, is present to His eyes. But if we cannot choose where we walk, why should those who take the narrow way of righteousness be rewarded in the next life while those who take the primrose path are consigned to the flames of hell? Theologians have not, of course, neglected this question. Augustine, for example, argued that God's foreknowledge (or more accurately, God's knowledge of what we call the future) doesn't cause events to happen and is therefore consistent with human free will. Other theologians have embraced the doctrine of predestination and argued that free will is indeed an illusion. Still others have taken the position that divine omniscience and human free will are compatible in a way that surpasses human understanding. Reconciling the scientific and ethical pictures of the world was a concern of the first scientists. Our scientific picture of the world was foreshadowed by Greek atomism, a theory invented by the natural philosophers Leucippus and Democritus in the fifth century B.C. According to this theory, the world is made up of unchanging, indestructible particles moving about in empty space and interacting with one another in a completely deterministic way. Like modern biologists, Democritus believed that we, too, are assemblies of atoms. Yet Democritus also elaborated a system of ethics based on moral responsibility. He taught that we should do what is right not from fear, whether of punishment or of public disapproval or of the wrath of gods, but in response to our own sense of right and wrong. Unfortunately, the surviving fragments of Democritus's writings don't tell us how or whether he was able to reconcile his deterministic picture of nature with his doctrine of moral responsibility. A century later, another Greek philosopher with similar ideas about physical reality and moral responsibility faced the same dilemma. Epicurus (341-270 B.C.) sought to reconcile human freedom with the atomic theory by postulating a random element in atomic interactions. Atoms, he said, occasionally "swerve" unpredictably from their paths. In modern times, Arthur Stanley Eddington and other scientists have put forward more sophisticated versions of the same idea. According to quantum physics, it is impossible to predict the exact moment when certain atornic events, such as the decay of a radioactive nucleus, will take place. Eddington believed that this kind of microscopic indeterminism might provide a scientific basis for human freedom:It is a consequence of the advent of quantum theory that physics is no longer pledged to a scheme of deterministic laws. . . . The future is a combination of the causal influences of the past together with unpredictable elements. . [S]cience thereby withdraws its moral opposition to free will.But neither Epicurus nor Eddington explained what the "freedom" enjoyed by a swerving atom or a radioactive atomic nucleus has to do with the freedom of a human being to choose between two courses of action. Nor has anyone else.

Layzer reaffirms his 1975 claim about the initial state of the universe lacking significant order or information, but he does not tell us that a theory of the growth of order goes back to the 1960's and is his original contribution.

We need not assume, as Clausius and Boltzmann did in the nineteenth century and - as many modern astronomers and physicists still do, that the Universe started out with a huge store of order that it has been gradually dissipating ever since. If the hypothesis outlined in this chapter is correct, the initial state of the Universe was wholly lacking in order.

In the concluding chapter of Cosmogenesis, Layzer revisits the problem of human freedom and especially creativity. Although he offers no resolution of the free will problem, he places great emphasis on an unpredictable creativity as the basis of both biological evolution and human activity in a universe with an open future.

Chance, Necessity, and Freedom To be fully human is to be able to make deliberate choices. Other animals sometimes have, or seem to have, conflicting desires, but we alone are able to reflect on the possible consequences of different actions and to choose among them in the light of broader goals and values. Because we have this capacity we can be held responsible for our actions; we can deserve praise and blame, reward and punishment. Values, ethical systems, and legal codes all presuppose freedom of the will. So too, as P. F. Strawson has pointed out, do "reactive attitudes" like guilt, resentment, and gratitude. If I am soaked by a summer shower I may be annoyed by my lack of foresight in not bringing an umbrella, but I don't resent the shower. I could have brought the umbrella; the shower just happened. Freedom has both positive and negative aspects. The negative aspects — varieties of freedom from — are the most obvious. Under this heading come freedom from external and internal constraints. The internal constraints include ungovernable passions, addictions, and uncritical ideological commitments. The positive aspects of freedom are more subtle. Let's consider some examples. 1. A decision is free to the extent that it results from deliberation. Absence of coercion isn't enough. Someone who bases an important decision on the toss of a coin seems to be acting less freely than someone who tries to assess its consequences and to evaluate them in light of larger goals, values, and ethical precepts. 2. Goals, values, and ethical precepts may themselves be accepted uncritically or under duress, or we may feel free to modify them by reflection and deliberation. Many people don't desire this kind of freedom and many societies condemn and seek to suppress it. Freedom and stability are not easy to reconcile, and people who set a high value on stability tend to set a correspondingly low value on freedom. But whether or not we approve of it, the capacity to reassess and reconstruct our own value systems represents an important aspect of freedom. 3. Henri Bergson believed that freedom in its purest form manifests itself in creative acts, such as acts of artistic creation. Jonathan Glover has argued in a similar vein that human freedom is inextricably bound up with the "project of self-creation." The outcomes of creative acts are unpredictable, but not in the same way that random outcomes are unpredictable. A lover of Mozart will immediately recognize the authorship of a Mozart divertimento that he happens not to have heard before. The piece will "sound like Mozart." At the same time, it will seem new and fresh; it will be full of surprises. If it wasn't, it wouldn't be Mozart. In the same way, the outcomes of self-creation are new and unforeseeable, yet coherent with what has gone before. Although philosophical accounts of human freedom differ, they differ surprisingly little. On the whole, they complement rather than conflict with one another. What makes freedom a philosophical problem is the difficulty of reconciling a widely shared intuitive conviction that human beings are or can be free (in the ways discussed above or in similar ways) with an objective view of the world as a causally connected system of events. We feel ourselves to be free and responsible agents, but science tells us (or seems to tell us) that we are collections of molecules moving and interacting according to strict causal laws. For Plato and Aristotle, there was no real difficulty. They believed that the soul initiates motion — that acts of will are the first links of the causal chains in which they figure. With few exceptions, modern neurobiologists have rejected the view of the relation between mind and body that this doctrine implies. They regard mental processes as belonging to the natural world, subject to the same physical laws that govern inanimate matter. The differences between animate and inanimate systems and between conscious, and nonconscious nervous processes are not caused by the presence or absence of nonmaterial substances (the breath of, life, mind, spirit, soul) but by the presence or absence of certain kinds of order. This conclusion is more than a profession of scientific faith. It becomes unavoidable once we accept the hypothesis of biological evolution, without which, as Theodosius Dobzhansky remarked, nothing in biology makes sense. The evolutionary hypothesis implies that human consciousness evolved from simpler kinds of consciousness, which in turn evolved from nonconscious forms of nervous activity. There is no point in this evolutionary sequence where mind or spirit or soul can plausibly be assumed to have inserted itself "from without." It seems even more implausible to suppose that it was there all along, although, as we saw earlier, some modem philosophers and scientists have held this view. Karl Popper and other philosophers have tried to resolve the apparent conflict between free will and determinism by attacking the most sacred of natural science's sacred cows, the assumption that all natural processes obey physical laws. In asserting that there may be phenomena that don't obey physical laws, these philosophers are obviously on safe ground. But the assumption of indeterminism doesn't really help. A freely taken decision or a creative act doesn't just come into being. It is the necessary — and hence law-abiding — outcome of a complex process. Free actions also have predictable — and hence lawful - consequences; otherwise, planning and foresight would be futile. Thus every free act belongs to a causal chain: it is the necessary outcome of a deliberative or creative process, and it has predictable consequences. Some physicists and philosophers have suggested that quantal indeterminacy may provide leeway for free acts in an otherwise deterministic Universe. Freedom, however, doesn't reside in randomness; it resides in choice. Plato and Aristotle were right in linking Chance and Necessity as "forces" opposed to design and purpose in the Universe. Strong Cosmological Principle

The Strong Cosmological Principle (SCP) is a speculative interpretation of quantum indeterminacy based on Einstein's idea that the probabilities of different experimental results are simply the frequencies of the different results in an "assembly" - a large number of identical experiments. In the Schrödinger's Cat thought experiment, for example, the SCP simply says that in a certain fraction of the experiments the cat is alive, in the remaining fraction, dead.

The SCP starts from Einstein's cosmological principle that the properties (and the physical laws) of the universe do not single out any particular place in the universe. Astronomical observations have confirmed that the average properties of the universe are the same everywhere in space and they are the same in all directions from any given point. The universe is statistically uniform and isotropic.

Layzer says that his interpretation of quantum theory differs from Einstein's in an important way.

Einstein believed that quantum theory applies to assemblies rather than to individual systems because individual systems are governed by as-yet undiscovered deterministic laws. I have argued that quantum theory applies to assemblies rather than to individual systems because a complete physical reality doesn't refer to individual systems but only to assemblies. The smallest fragment of the Universe we can meaningfully describe is an assembly. If the members of the assembly are in identical microstates, there is no harm in treating them as individuals. But if they are quantal systems coupled to (macroscopic) measuring devices, we run into paradoxes like those we have discussed when we assume that quantum theory applies to them directly as individuals. Free Will redux

Recently, Layzer imagines that a large assembly of similar situations in different regions of the infinite universe can provide an explanation for the problem of the macroscopic indeterminism needed for free will, without depending on microscopic quantum indeterminism.

In each individual system, everything is determined, but in the assembly of all systems, the Strong Cosmological Principle insures there will be a variety of objectively indeterminate outcomes.

Layzer says that the fact that we don't know which of the many possible systems we are in means that our future is indeterminate, more specifically that our current state has not been predetermined by the initial state of the universe.

Other Multiple World Ideas

In ancient times, Lucretius commented on possible worlds.

In his De Rerum Natura, he wrote in Book V,

for which of these causes holds in our world it is difficult to say for certain ; but what may be done and is done through the whole universe in the various worlds made in various ways, that is what I teach, proceeding to set forth several causes which may account for the movements of the stars throughout the whole universe; one of which, however, must be that which gives force to the movement of the signs in our world also; but which may be the true one,The idea of many possible worlds was also proposed by Gottfried Leibniz, who famously argued that the actual world is "the best of all possible worlds." Leibniz says to Arnauld in a letter from 14 July 1686, I think there is an infinity of possible ways in which to create the world, according to the different designs which God could form, and that each possible world depends on certain principal designs or purposes of God which are distinctive of it, that is, certain primary free decrees (conceived sub ratione possibilitatis) or certain laws of the general order of this possible universe with which they are in accord and whose concept they determine, as they do also the concepts of all the individual substances which must enter into this same universe.Leibniz' notion of a substance was so complete that it in principle could be used to deduce from it all the predicates of the subject (the "bundle" of all properties) to which this notion is attributed. Hugh Everett III's many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is an attempt to deny the random "collapse" of the wave function and preserve determinism in quantum mechanics. Everett claims that every time an experimenter makes a quantum measurement with two possible outcomes, the entire universe splits into two new universes, each with the same material content as the original, but each with a different outcome. It violates the conservation of mass/energy in the most extreme way. The Everett theory preserves the "appearance" of possibilities as well as all the results of standard quantum mechanics. It is an "interpretation" after all. So even wave functions "appear" to collapse. Note that if there are many possibilities, whenever one becomes actual, the others disappear instantly in standard quantum physics. In Everett's theory, they become other possible worlds. The human ignorance of not knowing which universe we are in Layzer calls a macroscopic indeterminism that does solve the free will problem. If Layzer is right, the logically possible worlds of David Lewis and the many worlds of physicist Hugh Everett also solve the free will problem.

Possible Worlds and Free Will

In our two-stage model of free will, we can imagine the alternative possibilities for action generated by an agent in the first stage to be "possible worlds." They are counterfactual situations in Saul Kripke's sense, involving a single individual.

Note that Kripke's possible worlds are extremely close to one another. The quantification of information in each case shows a very small number of bits as the difference between them, especially when compared to the typical examples given in possible worlds cases. In the case of Hubert Humphrey winning the 1968 presidential election, millions of persons must have done something different. Such worlds are hardly "nearby." For typical cases of a free decision, the possible worlds require only small differences in the mind of a single person.

By comparison, the possible worlds of Hugh Everett, David Lewis, and David Layzer in general may bear very little resemblance to one another. But note that they all include Layzer's solution to the problem of free will, at least in those worlds with thinking beings, because the inhabitants do not know which of all the possible worlds they are in.

Gerald Withrow on Layzer's arrows of time

In 1972 Whitrow published his book The Nature of Time in which he wrote...

Recently David Layzer of Harvard has made a fresh attempt to relate the three macroscopic arrows of time: the thermodynamic arrow, defined by entropy* processes in closed systems, the historical arrow, defined by in(ormation-generating processes in certain open systems, and the cosmological arrow, defined by the recession of the galaxies. Having pointed out the subtle difficulties associated with the thermodynamic arrow, he turns to the historical arrow provided by the evolutionary records which all point in the direction of increasing information. These records are produced not only by biological systems. A record of the Moon's past is written in its pitted surface; the internal structure of a star, like that of a tree, records the process of ageing; and the complicated forms we observe in spiral galaxies reflect the volutionary processes that shape them. We may define the historical arrow through the statement that 'the present state of the universe (or of any sufficiently large subsystem of it) contains a partial record of the past but none of the future.' Layzer sketches a theory that seeks to relate the thermodynamic and historical arrows with the cosmological one by deriving all three from a common postulate: that the spatial structure of the universe is statistically homogeneous and isotropic - in other words, no statistical property of the universe serves to define a specific direction or position in space. From this he deduces that a completed escription of the universe can be xpressed in statistical terms. For example, if a universe satisfying Layzer's postulate were in a state of thermodynamic equilibrium it would be completely characterized by its temperature and density, and all other bservable quantities could be calculated knowing only these. Layzer argues that thermodynamic equilibrium of the whole universe is only likely to be satisfied when the universe is close to a singular state of infinite density, which he defines as the initial state. The cosmic expansion then generates both entropy and information. He concludes that the world is unfolding in time and the future never wholly predictable, since the specific nformation content of the universe increases steadily from the initial singular state. Consequently, the present state of the universe cannot contain enough information to define any future state. 'The future grows from the past as a plant grows from a seed, yet it contains more than the past.'

Why We are Free

In March 2021, Layzer's third and final book, Why We are Free, was published, summarizing his thinking on free will.

You can download an interactive PDF here.

Or order a paperback or Kindle version from Amazon here.

David Layzer’s universe is creative. It is “cosmic evolution.” The universe as a whole is evolves and is

creative. Chemical evolution of atoms and molecules is creative. The evolution of stars and galaxies is creative. Biological evolution is creative. And "mental evolution" as William James called it, is also creative. Layzer was attracted to Henri Bergson's ideas about Creative Evolution (L'Evolution Creatrice).

Layzer took much of his inspiration from Albert Einstein, and often quoted Einstein’s famous observation that scientific theories are “free creations of the human mind.” Theories must all begin as novel ideas. To be new is to be not determined by past ideas, it must first involve indeterminism. First chance, then choice.

So of course, human minds are creative.

Layzer bases his “living world” on Ernst Mayr’s two-step creative process, with randomness in the first step and natural selection determining the outcome. Layzer’s libertarian free will also comes in the two stages described by William James, the first is the chance generation of alternative possibilities, the second is the decision and choice that grants consent to one possibility, making it actual. Layzer calls the second step deliberative, an act of self-determination.

Layzer and Einstein both knew the second step in science lies in experiments testing those possible ideas. A good theory generates the mathematical probability for each possibility. It then takes multiple experiments to develop the statistics that confirm or deny those theoretical probabilities.

Theories give us a priori probabilities about possibilities. Experiments give us the a posteriori statistics about actualities. In his lectures on probability and statistics, Layzer always stressed the law of large numbers as the reason that macroscopic regularities can appear out of microscopic randomness.

Mayr’s two steps and James’s two stages, both first free (indeterministic) then adequately determined, can explain Layzer’s “growth of order” in the universe at all levels from elementary particles to the multiverse.

Other I-Phi pages on Layzer's work

Layzer's papers

A Preface to Cosmogony, Astrophysical Journal 138 (1963) p.174 (PDF)

Cosmic Evolution and Thermodynamic Irreversibility, Pure. Appl. Chem. 22 (1970) pp.457-468 (PDF)

The Strong Cosmological Principle, Indeterminacy, and the Direction of Time, The Nature of Time. T. Gold, ed., Cornell University Press (1967) pp.111-120.

The Arrow of Time, Harvard Astronomy Department preprint (1971)

The Arrow of Time, Scientific American 233.6 (1975) pp.56-69. (PDF)

The Arrow of Time, Astrophysical Journal 206 (1976) pp.559-569. (PDF)

Quantum mechanics, thermodynamics, and the strong cosmological principle, Physics as Natural Philosophy, MIT Press (1982) (PDF)

"Growth of Order in the Universe," in Entropy, information and evolution: New perspectives on physical and biological evolution, Weber, Bruce H., et al. (1990) pp.23-39 (PDF)

Cosmology, initial conditions, and the measurement problem, arXiv preprint (2010) (PDF)

Naturalizing Libertarian Free Will, 2010 (unpublished Word doc)

Free Will as a Scientific Problem, 2011 (unpublished PDF)

Bibliography

Brooks, Daniel R., and E.O.Wiley, 1988, Evolution as Entropy, Univ. Chicago Press, p.11 +

Carroll, Sean, 2008. The Cosmic Origins of Time's Arrow, i>Scientific American June (2008) pp.48-57

Chaisson, Eric, 2001. Cosmic Evolution, Harvard University Press, p.129-30

Decadt, Yves, 2000, The Average Evolution (De Gemiddelde Evolutie)

Frautschi, S. 1982. "Entropy in an Expanding Universe," Science v.217, pp.593-599

__________, 1988. "Entropy in an Expanding Universe." in Entropy, Information, and Evolution, Weber, Bruce H., et al. (1990), MIT Press, p.12

Layzer, David, 1963, "A Preface to Cosmogony," Astrophysical Journal. v.138, p.174.

______, 1963, "The Strong Cosmological Principle, Indeterminacy, and the Direction of Time" in The Nature of Time, Cornell University Press, 1967 [the first presentation of SCP?, at Cornell in 1963]

______, 1970. "Cosmic Evolution and Thermodynamic Irreversibility," in Pure and Applied Chemistry 22:457. (Presentation in Cardiff, Scotland, 1965?)

______, 1971, "Cosmogonic Processes," in Astrophysics and General Relativity, two volumes, edited by Max Chrétien, Stanley Deser, and Jack Goldstein, Gordon and Breach, NY. [Summer institute at Brandeis, 1968 - the first appearance of Growth of Order?]

______, 1971, "The Arrow of Time," unpublished manuscript, June 24, 1971

______, 1975. "The Arrow of Time," Scientific American, December, pp.56-69.

______, 1976. "The Arrow of Time," Astrophysical Journal. v.206, p.559.

______, 1980. American Naturalist. v.115, p.809.

______, 1982. "Quantum mechanics, thermodynamics, and the strong cosmological principle," in

Physics as Natural Philosophy, A. Shimony and H. Feshbach, eds., MIT Press

______, 1984. Constructing the Universe. Scientific American Illustrated Library, chapter 8.

______, 1988. "Growth of Order in the Universe," in Entropy, Information, and Evolution, MIT Press, pp.23-39.

______, 1990. Cosmogenesis: The Growth of Order in the Universe. Oxford University Press. pp.140-45.

______, 2010. "Cosmology, Initial Conditions, and the Problem of Measurement." (arXiv)

______, 2010. "Naturalizing Libertarian Free Will" 2010 (Word doc) [submitted to Mind and Matter]

______, 2011. "Free Will as a Scientific Problem" (PDF)

Lestienne, Rémy, 1990. The Children of Time. U. Illinois Press, p.123.

_______________, 1993. The Creative Power of Chance. U. Illinois Press, p.108.

Roederer, Juan., 2005. Information and Its Role in Nature, Springer, p. 227.

Salthe, Stanley, 2004. "The Spontaneous Origin of New Levels in a Scalar Hierarchy," Entropy 2004, 6, 327-343

Wicken, Jeffery S., 1987. Evolution, Thermodynamics, and Information, Oxford University Press, p. 39.

In Memoriam

My Harvard teacher and colleague David Layzer died in 2019. He was my wife Holly's thesis adviser and he taught me probability and statistics in the 1960's.

In 1971 David circulated his first Arrow of Time manuscript, then in 1975 published his landmark article in Scientific American on the The Arrow of Time. This was the first publication of David's greatest contribution to cosmology, which explains the growth of order and information in the universe despite the second law of thermodynamics which demands that the disorder, the overall entropy, must also increase.

This made a great impression on my thinking. Since my undergraduate years at Brown, I had been inspired by Arthur Stanley Eddington's argument in his book The Nature of the Physical World (his Gifford Lectures), that entropy might somehow underlie human concepts of beauty and melody. Eddington wrote

Suppose that we were asked to arrange the following in two categories –From the 1950's I thought that negative entropy might be considered a measure of objective value in the universe, a radical thought in those days. When I developed my free will model in the 1970's I called it "Cogito," a term often used for the mind. Somewhat fancifully, I argued that "negative" entropy was a very positive concept and deserves a new name. I came up with "Ergo," reminiscent of symbols for freely available energy E0. And erg is a unit of energy. As a salute to the first modern philosopher, René Descartes, I chose "Sum"distance, mass, electric force, entropy, beauty, melody.I think there are the strongest grounds for placing entropy alongside beauty and melody and not with the first three. Entropy is only found when the parts are viewed in association, and it is by viewing or hearing the parts in association that beauty and melody are discerned. All three are features of arrangement. to complete the Peircean triad in the Information Philosopher tricolor logo.

The expansion creates new phase-space cells faster than atoms can distribute between them. This is the germ of David's explanation for the growth of order in the universe. Perhaps David did not read New Pathways?

The expansion of the universe creates new possibilities of distribution faster than the atoms can work through them, and there is no longer any likelihood of a particular distribution being repeated. For Teachers

|