|

Philosophers

Mortimer Adler Rogers Albritton Alexander of Aphrodisias Samuel Alexander William Alston Anaximander G.E.M.Anscombe Anselm Louise Antony Thomas Aquinas Aristotle David Armstrong Harald Atmanspacher Robert Audi Augustine J.L.Austin A.J.Ayer Alexander Bain Mark Balaguer Jeffrey Barrett William Barrett William Belsham Henri Bergson George Berkeley Isaiah Berlin Richard J. Bernstein Bernard Berofsky Robert Bishop Max Black Susanne Bobzien Emil du Bois-Reymond Hilary Bok Laurence BonJour George Boole Émile Boutroux Daniel Boyd F.H.Bradley C.D.Broad Michael Burke Jeremy Butterfield Lawrence Cahoone C.A.Campbell Joseph Keim Campbell Rudolf Carnap Carneades Nancy Cartwright Gregg Caruso Ernst Cassirer David Chalmers Roderick Chisholm Chrysippus Cicero Tom Clark Randolph Clarke Samuel Clarke Anthony Collins Antonella Corradini Diodorus Cronus Jonathan Dancy Donald Davidson Mario De Caro Democritus Daniel Dennett Jacques Derrida René Descartes Richard Double Fred Dretske John Earman Laura Waddell Ekstrom Epictetus Epicurus Austin Farrer Herbert Feigl Arthur Fine John Martin Fischer Frederic Fitch Owen Flanagan Luciano Floridi Philippa Foot Alfred Fouilleé Harry Frankfurt Richard L. Franklin Bas van Fraassen Michael Frede Gottlob Frege Peter Geach Edmund Gettier Carl Ginet Alvin Goldman Gorgias Nicholas St. John Green H.Paul Grice Ian Hacking Ishtiyaque Haji Stuart Hampshire W.F.R.Hardie Sam Harris William Hasker R.M.Hare Georg W.F. Hegel Martin Heidegger Heraclitus R.E.Hobart Thomas Hobbes David Hodgson Shadsworth Hodgson Baron d'Holbach Ted Honderich Pamela Huby David Hume Ferenc Huoranszki Frank Jackson William James Lord Kames Robert Kane Immanuel Kant Tomis Kapitan Walter Kaufmann Jaegwon Kim William King Hilary Kornblith Christine Korsgaard Saul Kripke Thomas Kuhn Andrea Lavazza James Ladyman Christoph Lehner Keith Lehrer Gottfried Leibniz Jules Lequyer Leucippus Michael Levin Joseph Levine George Henry Lewes C.I.Lewis David Lewis Peter Lipton C. Lloyd Morgan John Locke Michael Lockwood Arthur O. Lovejoy E. Jonathan Lowe John R. Lucas Lucretius Alasdair MacIntyre Ruth Barcan Marcus Tim Maudlin James Martineau Nicholas Maxwell Storrs McCall Hugh McCann Colin McGinn Michael McKenna Brian McLaughlin John McTaggart Paul E. Meehl Uwe Meixner Alfred Mele Trenton Merricks John Stuart Mill Dickinson Miller G.E.Moore Ernest Nagel Thomas Nagel Otto Neurath Friedrich Nietzsche John Norton P.H.Nowell-Smith Robert Nozick William of Ockham Timothy O'Connor Parmenides David F. Pears Charles Sanders Peirce Derk Pereboom Steven Pinker U.T.Place Plato Karl Popper Porphyry Huw Price H.A.Prichard Protagoras Hilary Putnam Willard van Orman Quine Frank Ramsey Ayn Rand Michael Rea Thomas Reid Charles Renouvier Nicholas Rescher C.W.Rietdijk Richard Rorty Josiah Royce Bertrand Russell Paul Russell Gilbert Ryle Jean-Paul Sartre Kenneth Sayre T.M.Scanlon Moritz Schlick John Duns Scotus Arthur Schopenhauer John Searle Wilfrid Sellars David Shiang Alan Sidelle Ted Sider Henry Sidgwick Walter Sinnott-Armstrong Peter Slezak J.J.C.Smart Saul Smilansky Michael Smith Baruch Spinoza L. Susan Stebbing Isabelle Stengers George F. Stout Galen Strawson Peter Strawson Eleonore Stump Francisco Suárez Richard Taylor Kevin Timpe Mark Twain Peter Unger Peter van Inwagen Manuel Vargas John Venn Kadri Vihvelin Voltaire G.H. von Wright David Foster Wallace R. Jay Wallace W.G.Ward Ted Warfield Roy Weatherford C.F. von Weizsäcker William Whewell Alfred North Whitehead David Widerker David Wiggins Bernard Williams Timothy Williamson Ludwig Wittgenstein Susan Wolf Xenophon Scientists David Albert Michael Arbib Walter Baade Bernard Baars Jeffrey Bada Leslie Ballentine Marcello Barbieri Gregory Bateson Horace Barlow John S. Bell Mara Beller Charles Bennett Ludwig von Bertalanffy Susan Blackmore Margaret Boden David Bohm Niels Bohr Ludwig Boltzmann Emile Borel Max Born Satyendra Nath Bose Walther Bothe Jean Bricmont Hans Briegel Leon Brillouin Stephen Brush Henry Thomas Buckle S. H. Burbury Melvin Calvin Donald Campbell Sadi Carnot Anthony Cashmore Eric Chaisson Gregory Chaitin Jean-Pierre Changeux Rudolf Clausius Arthur Holly Compton John Conway Simon Conway-Morris Jerry Coyne John Cramer Francis Crick E. P. Culverwell Antonio Damasio Olivier Darrigol Charles Darwin Richard Dawkins Terrence Deacon Lüder Deecke Richard Dedekind Louis de Broglie Stanislas Dehaene Max Delbrück Abraham de Moivre Bernard d'Espagnat Paul Dirac Hans Driesch John Dupré John Eccles Arthur Stanley Eddington Gerald Edelman Paul Ehrenfest Manfred Eigen Albert Einstein George F. R. Ellis Hugh Everett, III Franz Exner Richard Feynman R. A. Fisher David Foster Joseph Fourier Philipp Frank Steven Frautschi Edward Fredkin Augustin-Jean Fresnel Benjamin Gal-Or Howard Gardner Lila Gatlin Michael Gazzaniga Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen GianCarlo Ghirardi J. Willard Gibbs James J. Gibson Nicolas Gisin Paul Glimcher Thomas Gold A. O. Gomes Brian Goodwin Joshua Greene Dirk ter Haar Jacques Hadamard Mark Hadley Patrick Haggard J. B. S. Haldane Stuart Hameroff Augustin Hamon Sam Harris Ralph Hartley Hyman Hartman Jeff Hawkins John-Dylan Haynes Donald Hebb Martin Heisenberg Werner Heisenberg Grete Hermann John Herschel Basil Hiley Art Hobson Jesper Hoffmeyer Don Howard John H. Jackson William Stanley Jevons Roman Jakobson E. T. Jaynes Pascual Jordan Eric Kandel Ruth E. Kastner Stuart Kauffman Martin J. Klein William R. Klemm Christof Koch Simon Kochen Hans Kornhuber Stephen Kosslyn Daniel Koshland Ladislav Kovàč Leopold Kronecker Rolf Landauer Alfred Landé Pierre-Simon Laplace Karl Lashley David Layzer Joseph LeDoux Gerald Lettvin Gilbert Lewis Benjamin Libet David Lindley Seth Lloyd Werner Loewenstein Hendrik Lorentz Josef Loschmidt Alfred Lotka Ernst Mach Donald MacKay Henry Margenau Owen Maroney David Marr Humberto Maturana James Clerk Maxwell Ernst Mayr John McCarthy Warren McCulloch N. David Mermin George Miller Stanley Miller Ulrich Mohrhoff Jacques Monod Vernon Mountcastle Emmy Noether Donald Norman Travis Norsen Alexander Oparin Abraham Pais Howard Pattee Wolfgang Pauli Massimo Pauri Wilder Penfield Roger Penrose Steven Pinker Colin Pittendrigh Walter Pitts Max Planck Susan Pockett Henri Poincaré Daniel Pollen Ilya Prigogine Hans Primas Zenon Pylyshyn Henry Quastler Adolphe Quételet Pasco Rakic Nicolas Rashevsky Lord Rayleigh Frederick Reif Jürgen Renn Giacomo Rizzolati A.A. Roback Emil Roduner Juan Roederer Jerome Rothstein David Ruelle David Rumelhart Robert Sapolsky Tilman Sauer Ferdinand de Saussure Jürgen Schmidhuber Erwin Schrödinger Aaron Schurger Sebastian Seung Thomas Sebeok Franco Selleri Claude Shannon Charles Sherrington Abner Shimony Herbert Simon Dean Keith Simonton Edmund Sinnott B. F. Skinner Lee Smolin Ray Solomonoff Roger Sperry John Stachel Henry Stapp Tom Stonier Antoine Suarez Leo Szilard Max Tegmark Teilhard de Chardin Libb Thims William Thomson (Kelvin) Richard Tolman Giulio Tononi Peter Tse Alan Turing C. S. Unnikrishnan Nico van Kampen Francisco Varela Vlatko Vedral Vladimir Vernadsky Mikhail Volkenstein Heinz von Foerster Richard von Mises John von Neumann Jakob von Uexküll C. H. Waddington James D. Watson John B. Watson Daniel Wegner Steven Weinberg Paul A. Weiss Herman Weyl John Wheeler Jeffrey Wicken Wilhelm Wien Norbert Wiener Eugene Wigner E. O. Wilson Günther Witzany Stephen Wolfram H. Dieter Zeh Semir Zeki Ernst Zermelo Wojciech Zurek Konrad Zuse Fritz Zwicky Presentations Biosemiotics Free Will Mental Causation James Symposium |

Entanglement

Entanglement is a mysterious quantum phenomenon that is widely, but mistakenly, described as capable of transmitting information over vast distances faster than the speed of light. It has proved very popular with science writers, philosophers of science, and many scientists who hope to use the mystery to deny some of the basic concepts underlying quantum physics. Beyond this claim, which violates the principle of relativity, is the claim that entanglement "connects" every particle in the universe with every other particle, implying a "holistic" or "implicate" order in the universe, which is popular with "new age" thinkers and other mystics who see in it pan-psychism, or "cosmic consciousness," or at a minimum "telepathic powers" between entangled minds.

Entanglement depends on two quantum properties that are thought to be impossible in "classical" physics. One is called nonlocality. We shall argue that Albert Einstein first caught a glimpse of nonlocality as early as his photoelectric effect paper, published in June of 1905, when he questioned how a continuous light wave spread out in space could instantly collapse all its energy to become localized in the discrete quantum of energy needed to eject an electron. We call this "collapse" because it was the first insight into what the founders of quantum mechanics over twenty years later would call the "collapse of the wave function." At this early time, Einstein already said explicitly that the instantaneous relocation of the light wave appeared to violate his brand new relativity principle, published in September of that "miracle year."

Einstein again discussed the fundamental connection between a particle and its wave nature in 1909, when he said that physics in the future will require a "fusion" of the wave and particle pictures. Einstein saw the continuous light wave as a "ghost field" or "guiding field" somehow determining the probabilities of locating the discrete light quanta. That was years before Louis de Broglie argued that material particles have associated "pilot waves" (1924), leading Erwin Schrödinger to develop his wave function ψ and his wave mechanics (1926).

Einstein made a clear public statement about the connection between the wave function and the photon particle twenty-two years after his photoelectric effect paper, at the 1927 Solvay conference on "Electrons and Photons."

|ψ|2 expresses the probability that there exists at the point considered a particular particle of the cloud, for example at a given point on the screen.Einstein's remarks were misunderstood but well reported by Niels Bohr. These concerns of Einstein's about nonlocality were ignored by most physicists until 1935 and the appearance of the famous Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paper, in which Einstein feared there was some kind of "spooky action-at-a-distance." The other "impossible" quantum property is nonseparability, which Einstein also was first to see, even as he attacked the idea. Note that this negative reaction was just as Einstein had reacted to his unwelcome discovery of indeterminism in 1916, when he attacked the appearance of chance (Zufall) in the direction of emitted photons as a "weakness in the theory." Both ontological chance and the "holistic" nonseparability of particles described by a single wave function were first seen by Einstein long before they became standard elements in quantum mechanics. In 1933 Einstein suggested we can know the position or the momentum of one particle simply by measuring the position or momentum of another particle with which it had interacted in the past. Since it requires no interaction between the particles, we can call this "knowledge-at-a-distance." It depends only on the classical laws of motion and especially the conservation laws for energy, linear momentum, and angular momentum. In the 1935 EPR paper Einstein extended nonlocality beyond the relation between a light-quantum particle and its "wave function." Back in 1926 Erwin Schrödinger invented the "wave function" Ψ as the solution to his "wave equation." In 1927 Max Born had identified Ψ2 as the probability of finding a quantum particle somewhere, following a suggestion of Einstein in the early 1920's. Before 1933 the great difficulty was understanding the relationship between a single particle and its wave function Ψ. What Einstein did now was a thought experiment about two particles and their two-particle wave function Ψ12. It turned out that the two-particle wave function can not be separated into the product of two single-particle wave functions Ψ1 and Ψ2. Nonlocality was now extended by Einstein from a light particle and its light wave, to perfect "correlations" between one material particle and another with which it had interacted in the past. In his response to the EPR paper, Schrödinger called particles with such correlated properties "entangled" and he told Einstein about the necessary conditions under which Ψ12 could be "separated" into Ψ1 and Ψ2. After separation, they would be disentangled and decohered.

Einstein's Discovery of Nonlocality and Nonseparability

Einstein was the first to see nonlocal behavior in quantum phenomena. He may have seen it as early as 1905 in the photoelectric effect, the same year he published his special theory of relativity. But it was perfectly clear to him 22 years later (ten years after his general theory of relativity and his explanation of how quanta of light are randomly emitted and absorbed by atoms), when he described nonlocality with a diagram on the blackboard at an international conference of physicists in Belgium in 1927 at the fifth Solvay conference.

In his contribution to the 1949 Schilpp memorial volume on Einstein, Niels Bohr gave us a picture of what Einstein drew on that blackboard.

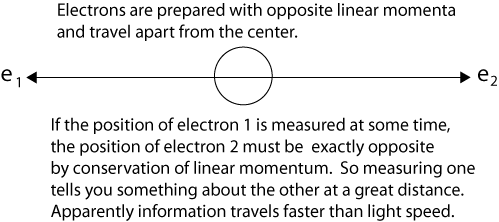

At the general discussion in Como, we all missed the presence of Einstein, but soon after, in October 1927, I had the opportunity to meet him in Brussels at the Fifth Physical Conference of the Solvay Institute, which was devoted to the theme "Electrons and Photons."Bohr is telling us that in 1927 Einstein saw instantaneous "correlations" of events widely separated ("as if actions-at-a-distance"), which exactly describes today's perfect "nonlocal" correlations of widely separated entangled particles. Later. in 1935, Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen proposed a thought experiment (known by their initials as EPR) to exhibit internal contradictions in the new quantum physics. They hoped to show that quantum theory could not describe certain intuitive "elements of reality" and thus was either incomplete or, as they might have hoped, demonstrably incorrect. Einstein and his colleagues Erwin Schrödinger, Max Planck, and others hoped for a return to deterministic physics, and the elimination of mysterious quantum phenomena like superposition of states and "collapse" of the wave function. EPR continues to fascinate determinist philosophers of science hoping to prove that quantum indeterminacy (ontological randomness) does not exist. Beyond the problem of nonlocality, the EPR thought experiment introduced the problem of "nonseparability." In his response to the EPR paper, Schrödinger in 1935 told Einstein that his "separability principle" (Trennungsprinzip) was simply wrong. Schrödinger's two-particle wave function Ψ12 can not be separated into the product of single-particle wave functions Ψ1 and Ψ2. The two particles share some properties. Instantaneous (simultaneous) knowledge of a distant particle's property (position or momentum or spin) can be gained by measurement of the same property of a local particle that interacted with the distant particle sometime in the past. The 1935 EPR paper was based on an earlier question of Einstein's about two particles fired toward one another with equal and opposite velocities. He imagined them starting at t0 some distance apart and approaching one another with equal high velocities. Then for a short time interval from t1 to t1 + Δt the particles are in contact with one another. Einstein described this situation to Léon Rosenfeld in 1933. Shortly before he left Germany to emigrate to America, Einstein attended a lecture on quantum electrodynamics by Rosenfeld. Keep in mind that Rosenfeld was perhaps the most dogged defender of the Copenhagen Interpretation, which maintains that a particle has no properties until it is measured. After the talk, Einstein asked Rosenfeld, “What do you think of this situation?” Suppose two particles are set in motion towards each other with the same, very large, momentum, and they interact with each other for a very short time when they pass at known positions. Consider now an observer who gets hold of one of the particles, far away from the region of interaction, and measures its momentum: then, from the conditions of the experiment, he will obviously be able to deduce the momentum of the other particle. If, however, he chooses to measure the position of the first particle, he will be able tell where the other particle is.We can diagram a simple case of Einstein’s question as follows after the particles have interacted at the center, using indistinguishable electrons rather than generic particles.

Recall that it was Einstein who discovered in 1924 the identical nature, indistinguishability, and interchangeability of some quantum particles. He found that identical particles are not independent, altering their quantum statistics.

After the particles interact at t1, quantum mechanics describes them with a single two-particle wave function Ψ12 that is not the product of independent single-particle wave functions Ψ1 and Ψ2. In the case of electrons, which are indistinguishable interchangeable particles, it is not proper to say electron 1 goes this way and electron 2 that way. (Nevertheless, it is convenient to label the particles, as we do in the illustration.)

Einstein then asked Rosenfeld, “How can the final state of the second

particle be influenced by a measurement performed on the first

after all interaction has ceased between them?” This was the germ

of the EPR paradox, and ultimately the problem of two-particle

entanglement.

Why does Einstein question Rosenfeld and describe this as an

“influence,” suggesting what he will later call a spooky “action-at-a-distance?”

It is only paradoxical in the context of Rosenfeld’s Copenhagen

Interpretation. The second particle is not itself measured and

yet we know something about its properties. The Copenhagen Interpretation

says we cannot know properties without an explicit measurement. They say some properties don't even exist until after a measurement.

Einstein was clearly correct to tell Rosenfeld that at a later time t2, a measurement of one particle's position would instantly establish the position of the other particle - without measuring it. Einstein obviously was using conservation of linear momentum implicitly to calculate (and know) the position of the second particle. But this not need be "action-at-a-distance." It is more likely simply "knowledge-at-a-distance."

Conservation laws are principles that are much deeper than classical mechanical laws or quantum mechanics. They are the consequence of symmetries in the motions.

Einstein's particles that have the same, but opposite, momentum move apart like mirror images of one another. Newton's first law of motion says that they will continue their motions unless some interaction disturbs them. No "influence" or action-at-a-distance by one particle on the other is needed for the motion of the particles to remain symmetric mirror images. It is precisely the lack of interactions that maintains the conservation of momentum.

Shortly after EPR, Schrödinger described two such particles as becoming "entangled" (verschränkt) at their first interaction, so "nonlocal" phenomena are also known as "quantum entanglement."

Although conservation laws are rarely cited as the explanation, they are the physical reason that entangled particles always produce correlated results for all properties. If the results were not always correlated, the implied violation of a fundamental conservation law would cause a much bigger controversy than entanglement itself, as puzzling as that is.

This idea of something measured in one place "influencing" measurements far away challenged what Einstein thought of as "local reality." It came to be known as "nonlocality." Einstein called it a "spukhaft Fernwirkung" or "spooky action at a distance."

We prefer to describe this phenomenon as "knowledge at a distance." No action has been performed on the distant particle simply because we learn about its position (or spin). Note that this assumes the distant particle has not been disturbed by an intermediate interaction (e.g., decoherence) with the environment after the original entanglement.

Note that it was David Bohm in 1952 who proposed Einstein's problem use electrons. Today many if not most accounts of the EPR paradox describe it with electrons.

What Would "Action-At-A-Distance" Require?

Where EPR used correlated positions of the two particles, modern examples follow David Bohm's correlated electron spins. We can ask how the measurement of one particle could possibly influence" or "act on" its distant companion to cause its position or its spin to become correlated perfectly, should it not already be correlated, as we argue, by the symmetry of conservation principles.

No correlations between properties of particles at the "separated" positions would mean that 1) in EPR their positions would not be exactly opposite and equidistant from the initial entanglement position, and 2) in Bohm's version, their spins are not exactly opposite in direction, conserving total spin zero of teh original spherically symmetric singlet state of the molecule.

How would action-at-a-distance then work to create correlations?

The first particle would have to measure the actual position or spin of the distant particle. Next, the first particle would by mechanical means have to change those distant properties to become correlated with itself. The interaction would have to "do work" on the distant particle and accomplish these steps "instantaneously," that is to say these mechanical operations would have to be achieved at speeds much greater than light speed.

There is nothing in classical or quantum mechanics that suggests this kind of remote interaction. There is no conceivable communication or signal that could tell the distant particle how exactly it must change itself. There is no self-action by which the second particle can change its own state when told to do so by the first, upon receiving the information about their differences.

Can Particles Have Specific Properties Determined Before They Are Measured? No. But Perfectly Correlated Indeterministic (Random) Properties Can Be Created By The Measurements, As Long As Alice And Bob Measure In Exactly the Same Direction, Preserving The Symmetry

In classical mechanics, the second EPR particle always does have the exact position needed to conserve linear momentum. In that case, Einstein was right. For quantum mechanics, however, Heisenberg's uncertainty principle limits the position (and momentum) accuracy. Podolsky and Rosen may have hoped to use EPR to deny the uncertainty principle. Einstein criticized their clumsy attempt.

For Bohm's spin measurements, the situation is more complex. It is impossible for the particles before measurement to have known spin in all three possible measurement directions, let alone in the direction (angle) Alice and Bob plan to measure. When spin is known/measured in the x-direction, spin in the y- and z-directions becomes indeterminate.

So can the spins be initially entangled in the exact direction that Alice or Bob choose to measure? No/ There are two problems with this assumption of a preferred direction created during the initial entanglement.

1) If Alice and Bob are free to choose their measurement direction, there is little chance they would choose that preferred initial direction. If they measure at an angle θ to that direction, correlations will no longer be perfect, falling off as the cosine of the angle θ, with no correlation at all for θ = 90°. Since Alice and Bob get perfect correlations in any direction, assuming they agree in advance on the direction and both measure in their chosen direction, there appears to be no initial preferred direction. The symmetry before their measurement is preserved by their symmetric measurements in the same direction.

2) The initial entangled state has total spin zero (the so-called singlet state). It is rotationally symmetric, isotropic, the same in all directions. If there were an initial preferred direction, that rotational symmetry would be destroyed. If there had been an initial preferred direction, it could not be known to Alice and Bob.

We will see how the perfect rotational symmetry of the initial entangled state with total spin zero can provide the explanation for Alice and Bob getting perfect (but random) correlations whatever their choice of measurement angle.

Their choice of a measurement direction breaks the rotational symmetry (in all directions) of the initial total spin zero state. But it preserves the planar symmetry (and total spin zero) in their pre-agreed-upon chosen direction, conserving total spin angular momentum. If it did not, a conservation law would have been violated. That cannot be. Conservation is a principle deeper than mere mechanical laws, classical or quantum.

We can say that a joint (shared) property of total spin zero existed before (and then after) their measurements. It existed in all directions and at all times. What did not exist before their measurements is the random up-down or down-up result of their measurements.

Erwin Schrödinger's two-particle wave function describes the two entangled particles as in a linear combination (a superposition) of up-down and down-up states. Their measurement randomly produces one of these states.

This is the sense in which observers "create reality" with an experimental measurement. Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg made the "free choice" as to what to measure a central element of their Copenhagen Interpretation. Alice and Bob freely choose the direction in which they measure. But whether their measurement outcomes are up-down or down-up is totally random (indeterministic). Paul Dirac called this "Nature's choice," not controllable by the experimenters but caused/created by their measurements.

The "free choice" of direction breaks the rotational symmetry of the total spin zero state. But it preserves the planar symmetry defined by Alice and Bob's (pre-agreed upon) measurement direction. This preserves the symmetry needed to conserve angular momentum in the chosen direction. But "Nature's choice" of outcome, whether Alice up-Bob down or Alice down-Bob up, creates the random but perfectly correlated spin properties that the Copenhagen Interpretation correctly says did not exist before the measurement.

Our analysis shows these random properties could not have existed at the initial entanglement. They are brought into existence by the experimenters' "free choice."

So the conservation of angular momentum alone can explain the perfect correlation of entangled electron spins with no needed faster-than-light interaction "at a distance" between the particles, as long as Alice and Bob measure in their previously agreed upon chosen direction.

Particles do not have the exact properties needed before the measurements. Quantum theory and the conservation principle predicts that measurements in a pre-agreed-upon direction can create perfectly correlated random properties. And thousands of Bell's theorem test experiments have confirmed that theory, explaining how perfectly correlated random bit strings can be created by Alice and Bob at vastly separated places, without any "spooky action-at-a-distance," just what is needed for quantum cryptography.

A Hidden Constant?

Because the conservation of total spin angular momentum is true from the moment of entanglement state preparation until after the measurements by Alice and Bob at arbitrarily large separations (as long as no external interactions take place), we describe the conserved total spin as providing a "hidden constant of the motion." Physicists from David Bohm to John Bell hoped to find "hidden variables" that could travel with the entangled particles, to ensure that their spins would be found opposite to one another.

The principle of conservation of angular momentum together with the experimental fact that spins in Bell test experiments are always found opposite one another gives us confidence that, although the (random) spin directions are unknown, they are opposite in the moment before measurements by Alice and Bob and thus opposite when measured.

See our hypothesis of a Hidden Constant of the Motion, all that is necessary to explain entanglement without superluminal "spooky action-at-a-distance."

Perhaps "hidden constant" is too cute, although it travels along with the particles just as David Bohm's hidden variables or David Mermin's "instruction sets" do.

A more modest name might be a common cause in the past history of the two particles.

Disentanglement

In the year following the Einstein-Podsky-Rosen paper, Erwin Schrödinger looked more carefully at Einstein's "separability" assumption (Trennungsprinzip) that an entangled system can be separated enough to be regarded as two systems with independent wave functions.

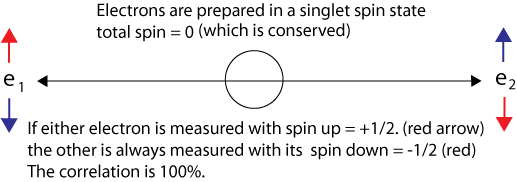

Years ago I pointed out that when two systems separate far enough to make it possible to experiment on one of them without interfering with the other, they are bound to pass, during the process of separation, through stages which were beyond the range of quantum mechanics as it stood then. For it seems hard to imagine a complete separation, whilst the systems are still so close to each other, that, from the classical point of view, their interaction could still be described as an unretarded actio in distans. And ordinary quantum mechanics, on account of its thoroughly unrelativistic character, really only deals with the actio in distans case. The whole system (comprising in our case both systems) has to be small enough to be able to neglect the time that light takes to travel across the system, compared with such periods of the system as are essentially involved in the changes that take place...Schrödinger says that the entangled system may become disentangled (Einstein's separation) and yet some perfect correlations between later measurements might remain. Note that the entangled system could simply decohere as a result of interactions with the environment, as proposed by decoherence theorists. The perfectly correlated results of Bell-inequality experiments might nevertheless be preserved, depending on the interaction. Schrödinger tells us that the two-particle wave function Ψ12 will be disentangled into the product of single-particle wave functions Ψ1 and Ψ2 by a measurement of either particle, for example, by either Alice's or Bob's measurements in the case of Bell's Theorem. As we saw, Einstein had objected to nonlocal phenomena as early as the Solvay Conference of 1927, when he criticized the collapse of the wave function as "instantaneous-action-at-a-distance" that prevents the wave from "acting at more than one place on the screen." The simultaneous events at points A and B in Einstein's 1927 Figure 1 above are the same kind of nonlocality as the two entangled particles acquiring perfectly correlated properties while in a spacelike separation that he suggested to Rosenfeld in 1933, and which Podolsky and Rosen developed into the EPR paradox in 1935. Einstein's 1927 concern was based on the idea that the light wave might contain some kind of ponderable energy. At that time Schrödinger thought it might be distributed electricity. In these cases the instantaneous "collapse" of the wave function might violate Einstein's principle of relativity, a concern he first expressed in 1909. When we recognize that the wave function is only pure information about the probability of finding a particle (or particles) somewhere, we see that there is no matter or energy (or in particular no information or signal of any kind) traveling faster than the speed of light in the so-called "collapse." Einstein's criticism somewhat resembles the criticisms by Descartes and others about Newton's theory of gravitation. Newton's opponents charged that his theory was "action at a distance" and instantaneous. Einstein's own theory of general relativity shows that gravitational influences travel at the speed of light and are mediated by a gravitational field that can be described as curved space-time. When a probability function collapses to unity in one place and zero elsewhere, nothing physical is moving from one place to the other. When the nose of one horse crosses the finish line, its probability of winning goes to certainty, and the finite probabilities of the other horses, including the one in the rear, instantaneously drop to zero. This happens faster than the speed of light, since the last horse is in a "space-like" separation. But this does not violate relativity. Only abstract "information" or "knowledge" is changing. The first practical and workable experiments to test the 1935 "thought experiments" of Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen (EPR) were suggested by David Bohm in 1952. Instead of measuring linear momentum, Bohm proposed using two hydrogen atoms that are prepared in an initial state of known total spin angular momentum zero. Momentum and position are continuous variables. Spin is discrete. Bohm argued that measurements of discrete variables would be more precise. Bohm also proposed local "hidden variables" might be needed to explain the correlations. Here is Bohm's description We consider a molecule of total spin zero consisting of two atoms, each of spin one-half. The wave function of the system is thereforeNote that when Bohm says "because the total spin is still zero, it can immediately be concluded that the same component of the spin of the other particle (B) is opposite to that of A," he is implicitly using the conservation of total spin. Can you see that our "hidden" constant of the motion hypothesis is implicit in Bohm's description? In 1964, John Bell put limits on Bohm's "hidden variables" that might restore a deterministic physics in the form of what he called an inequality, the violation of which would confirm standard quantum mechanics. Here is Bell's description. As with Bohm, conservation is not mentioned explicitly, but it involves spin components measured in the same direction at A and B. With the example advocated by Bohm and Aharonov, the EPR argument is the following. Consider a pair of spin one-half particles formed somehow in the singlet spin state and moving freely in opposite directions. Measurements can be made, say by Stern-Gerlach magnets, on selected components of the spins σ1 and σ2. If measurement of the component σ1 • a, where a is some unit vector, yields the value + 1 then, according to quantum mechanics, measurement of σ2 • a must yield the value — 1 and vice versa. Now we make the hypothesis, and it seems one at least worth considering, that if the two measurements are made at places remote from one another the orientation of one magnet does not influence the result obtained with the other.In his 1980 book, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, Bohm emphasized even more strongly that no interaction between particles is needed Consider a molecule of zero total spin, consisting of two atoms of spin ℏ/2. Let this molecule be disintegrated by a method not influencing the spin of either atom. The total spin then remains zero, even while the atoms are flying apart and have ceased to interact appreciably. Now, if any component of the spin of one of the atoms (say A) is measured, then because the total spin is zero, we can immediately conclude that this component of the spin of the other atom (B) is precisely opposite. Thus, by measuring any component of the spin of the atom A, we can obtain this component of the spin of atom B, without interacting with atom B in any way...The two spins are correlated and this permits us to know the spin of atom B when we measure that of A. Bohm and Bell are implicitly using the conservation of total spin, supporting our "hidden constant" hypothesis. If one electron spin is ℏ/2 in the up direction and the other is spin down or -ℏ/2, the total spin is zero. The underlying physical law of importance is not conservation of linear momentum (as Einstein used in EPR). Bohm and Bell use the conservation of angular momentum (or spin). If electron 1 is prepared with spin down and electron 2 with spin up, the total angular momentum is zero. This is called the singlet state.

| ψ > = 1/√2) | + - > - 1/√2) | - + > (1)

The principles of quantum mechanics say that the prepared system is in a linear combination (or superposition) of these two states, and can provide only the probabilities of finding the entangled system in either the | + - > state or the | - + > state.

The 1/√2 coefficients of the probability amplitude for each term, when squared, give us the probabilities (1/2) that the system will be found in the state | + - > or in the state | - + >. The actual outcome is random (Paul Dirac called it "Nature's choice." But the individual electron spin outcomes are not individually and separately random, because the particles are not independent. One is always up and the other down, as the conservation law and our "hidden constant" hypothesis require.

Should measurements ever show both spins in the same state, either | + + > or | - - >, that would violate the conservation of angular momentum. Quantum mechanics does not include such terms in the wave function. So they are not predicted and they are never observed, when measurements by Alice and Bob are made in the pre-agreed upon same direction.

EPR tests can be done more easily with polarized photons than with electrons, which require a vacuum and complex magnetic fields. The first of these was done in 1972 by Stuart Freedman and John Clauser at UC Berkeley. Their data, in agreement with quantum mechanics, violated the Bell's inequalities to high statistical accuracy, thus providing strong evidence against local hidden-variable theories. If hidden variables exist, they must be non-local, said Bell.

For more on superposition of states and the physics of photons, see the Dirac 3-polarizers experiment.

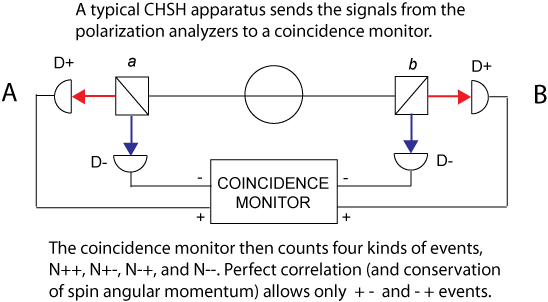

John Clauser, Michael Horne, Abner Shimony, and Richard Holt (known collectively as CHSH) and later Alain Aspect did more sophisticated tests. The outputs of the polarization analyzers were fed to a coincidence detector that records the instantaneous measurements, described as + -, - +, + +, and - - . The first two ( + - and - + ) conserve the spin angular momentum and are the only types ever observed in these nonlocality/entanglement tests, when measurements are made in the same direction.

How Information Physics Explains Nonlocality, Nonseparability, and Entanglement

Information physics starts with the fact that measurements bring new stable and irreversible information into existence. In EPR the information in the prepared state of the two particles includes the fact that the total linear momentum and the total angular momentum are zero.

New information requires an irreversible process that also increases the entropy more than enough to compensate for the information increase, to satisfy the second law of thermodynamics. It is this moment of irreversibility and the creation of new observable information that is the "cut" or Schnitt" described by Werner Heisenberg and John von Neumann in the famous problem of measurement

Note that the new observable information does not require a "conscious observer" as Eugene Wigner and some other scientists thought. The information is ontological (really in the world) and not merely epistemic (in the mind). Without new information encoded in the world, there would be nothing for the observers to observe.

Initially Prepared Information Plus Conservation Laws

Conservation laws are the consequence of extremely deep properties of nature that arise from simple considerations of symmetry. We regard these laws as "cosmological principles." Physical laws do not depend on the absolute place and time of experiments, nor their particular direction in space. Conservation of linear momentum depends on the translation invariance of physical systems, conservation of energy the independence of time, and conservation of angular momentum the invariance under rotations. Conservation laws are the consequence of symmetries, as explained by Emmy Noether.

Recall that the EPR experiment (Bohm version) starts with two electrons (or photons) prepared in an entangled state that is a mixture of pure two-particle states, each of which conserves the total angular momentum and, of course, conserves the linear momentum as in Einstein's original EPR example. This information about the linear and angular momenta is established by the initial state preparation (a measurement).

Quantum mechanics describes the probability amplitude wave function Ψ12 of the two-particle system as in a superposition of two-particle states. It is not a product of single-particle states, and there is no information about the identical indistinguishable electrons traveling along distinguishable paths. With slightly different notation, we can write equation (1) as

Ψ12 = 1/√2) | 1+2- > + 1/√2) | 1-2+ > (2)

The probability amplitude wave function Ψ12 travels away from the source (at the speed of light or less). Let's assume that at t0 observer A finds an electron (e1) with spin up.

At the time of this "first" measurement, by observer A or B, new information comes into existence telling us that the wave function Ψ12 has "collapsed" into the state | 1+2- > (or into | 1-2+ >). Just as in the two-slit experiment, probabilities have now become certainties, one possibility is now an actuality. If the first measurement finds a particular component of electron 1 spin is up, so the same spin component of entangled electron 2 must be down to conserve angular momentum. And conservation of linear momentum tells us that at t0 the second electron is equidistant from the source in the opposite direction.

It was simply determined by her measurement.

Why do so few accounts of entanglement mention conservation laws?

Although Einstein mentioned conservation in the original EPR paper, it is noticeably absent from later work. Bohm and Bell are obviously using it without an explicit mention. A prominent exception is Eugene Wigner, writing on the problem of measurement in 1963:

If a measurement of the momentum of one of the particles is carried out — the possibility of this is never questioned — and gives the result p, the state vector of the other particle suddenly becomes a (slightly damped) plane wave with the momentum -p. This statement is synonymous with the statement that a measurement of the momentum of the second particle would give the result -p, as follows from the conservation law for linear momentum. The same conclusion can be arrived at also by a formal calculation of the possible results of a joint measurement of the momenta of the two particles.

Visualizing Entanglement and Nonlocality

Schrödinger said that his "Wave Mechanics" provided more "visualizability" (Anschaulichkeit) than the Copenhagen school and its "damned quantum jumps" as he called them. He was right.

But we must focus on the probability amplitude wave function of the prepared two-particle state, and not attempt to describe the paths or locations of independent particles - at least until after some measurement has been made. We must also keep in mind the conservation laws that Einstein used to discover nonlocal behavior in the first place. Then we can see that the "mystery" of nonlocality is primarily the same mystery as the single-particle collapse of the wave function.

As Richard Feynman said, there is only one mystery in quantum mechanics (the collapse of probability and the consequent statistical outcomes).

We choose to examine a phenomenon which is impossible, absolutely impossible, to explain in any classical way, and which has in it the heart of quantum mechanics. In reality, it contains the only mystery. We cannot make the mystery go away by "explaining" how it works. We will just tell you how it works. In telling you how it works we will have told you about the basic peculiarities of all quantum mechanics.In his 1935 paper, Schrödinger described the two particles in EPR as "entangled" in English, and verschränkt in German, which means something like cross-linked. It describes someone standing with arms crossed. In the time evolution of an entangled two-particle state according to the Schrödinger equation, we can visualize it - as we visualize the single-particle wave function - as collapsing when a measurement is made. The discontinuous "jump" is also described as the "reduction of the wave packet." This is apt in the two-particle case, where the superposition of | + - > and | - + > states is "projected" or "reduced: to one of these states, and then further reduced to the product of independent one-particle states | + > and | - >. In the two-particle case (instead of just one particle making an appearance), when either particle is measured we know instantly those properties of the other particle that satisfy the conservation laws, including its location equidistant from, but on the opposite side of, the source, and its other properties such as spin. Here is an animation showing the two particles simultaneously acquiring their opposite spins when either is measured.

How Mysterious Is Entanglement?

Some commentators say that nonlocality and entanglement are a "second revolution" in quantum mechanics, "the greatest mystery in physics," or "science's strangest phenomenon," and that quantum physics has been "reborn." They usually quote Erwin Schrödinger as saying

"I consider [entanglement] not as one, but as the characteristic trait of quantum mechanics, the one that enforces its entire departure from classical lines of thought."Schrödinger knew that his two-particle wave function Ψ12 cannot have the same simple interpretation as the single particle, which can be visualized in ordinary 3-dimensional configuration space. And he is right that entanglement exhibits a richer form of the "action-at-a-distance" and nonlocality that Einstein had already identified in the "collapse" of the single particle wave function. But the main difference is that on measurement two particles acquire new properties instead of one particle, and they do it instantaneously (simultaneously), just as the single-particle wave function changes instantly over large volumes in the case of a single-particle measurement. Nonlocality and entanglement are thus another manifestation of Richard Feynman's "only" mystery in the two-slit experiment.

Is There an Asymmetry Here?

Here we must explain the asymmetry that Einstein and Schrödinger have introduced into a perfectly symmetric situation, making entanglement such a mystery. Every follower of their early thinking introduces this false asymmetry.

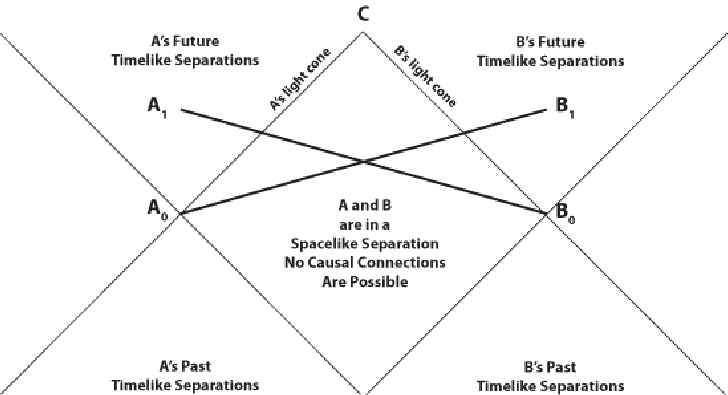

The classic EPR idea is completely symmetric about the origin of the state preparation. Einstein introduced the mistaken idea of measuring one particle "first" and then asking how it influences subsequent measurements of the "second" particle. By contrast, Schrödinger's two-particle wave function "collapses" at all positions in an instant of time. Both particles then appear in a space-like separation.

The perfectly symmetric picture shows that neither Alice nor Bob can in any way influence the other's experiment, as can be seen best in what we can call a special frame.

There is a special frame in which the collapse of the two-particle wave function is best visualized. It is not a preferred frame in the special relativistic sense (e.g., an inertial frame). But observers in all other frames in relative motion along the experiment axis will see one of the measurements before the other. Relativity contributes confusion to what is going on.

Almost every presentation of the EPR paradox begins with something like "Alice observes one particle..." and concludes with the question "How does the second particle get the information needed so that Bob's measurements correlate perfectly with Alice?"

There is a fundamental asymmetry in this framing of the EPR experiment. It is a surprise that Einstein, who was so good at seeing deep symmetries, did not consider how to remove the asymmetry. Even more puzzling, why did he introduce it? Why do most all subsequent scientists accept it without question?

Consider this reframing: Alice's measurement collapses the two-particle wave function. The two indistinguishable particles simultaneously appear at locations in a space-like separation. The frame of reference in which the source of the two entangled particles and the two experimenters are at rest is a special frame in the following sense.

As Einstein knew very well, there are frames of reference moving with respect to the laboratory frame of the two observers in which the time order of the events can be reversed. In some moving frames Alice measures first, but in others Bob measures first.

If there is a special frame of reference (not a preferred frame in the relativistic sense), surely it is the one in which the origin of the two entangled particles is at rest. Assuming that Alice and Bob are also at rest in this special frame and equidistant from the origin, we arrive at the simple picture in which any measurement that causes the two-particle wave function to collapse makes both particles appear simultaneously at determinate places with fully correlated properties (just those that are needed to conserve energy, momentum, angular momentum, and spin).

No "Hidden Variables," But Perhaps A "Hidden Constant?"

Although we find no need for "hidden variables," whether local or non-local, we might say that the conservation laws give us a "hidden constant." Conservation of a particular property is often described as a "constant of the motion." Such a constant might be viewed as "local," in that it travels along with the particles as a shared property, true at all times, or as "global," in that it is a property of the two-particle probability amplitude wave function Ψ12 as it spreads out in space.

This agrees with Bohm, and especially with Bell, who says that if the spin of particle 1 is measured to be up, then particle 2 is "predetermined" to be found to be down (if, and only if,

the two particles are measured in the same direction).

But recall that the Copenhagen Interpretation says we cannot know a spin property until it is measured. So some claim that both spins are in an unknown value of spin or and spin up until the measurements. It is this that suggests the possibility that both spins might be found in the same direction, both up or both down, which would violate the conservation laws.

Since electron spins in this situation are never found experimentally in the same direction, this gave rise to the idea of a hidden variable as some sort of signal that could travel to particle 2 after the measurement of particle 1, causing it to change its spin to be opposite that of particle 1. What sort of signal might this be? And what mechanism exists in a bare electron that could cause it to change a property like its spin without an external force of some kind?

Clearly, Wigner's explicit view that a conservation law is operating, and the implicit claims of Bohm and Bell that the electron spins were created in opposite states, are the simplest and clearest explanations of the entanglement mystery.

Despite accepting that a particular value of some "observables" can only be known by a measurement (knowledge is an epistemological problem) Einstein asked whether the particle actually (really, ontologically) paths and positions, even other properties, before we measure this? His answer was yes.

Einstein might have thought that the two particles have had their spins predetermined from the time of their entangling interaction. But as we have shown, the perfectly correlated properties were not created at the initial entanglement preparation but at the measurements by Alice and Bob, who freely chose an agreed upon direction to measure.

What must pre-exist is the jointly shared property of conserved total spin angular momentum zero in all directions, a symmetry property of the initial entanglement of the two particles, so that whatever direction is freely chosen, the result will be opposite spins to maintain total spin zero, either + -, or - +.

Note that if Alice and Bob were to measure at angles differing by an angle θ, the perfect correlations would be reduced by cos2θ. That would introduce measurements of + + and - -, which violate the conservation of total spin zero, proportional to sin2θ.

Why Pre-Determination Is Not Possible At Initial State Preparation

The simple and intuitive idea that the two particles acquired their specific opposite spins when they were prepared, at the moment of entanglement interaction above is unfortunately wrong. Quantum theory tells us that the spins of both particles are undetermined in all directions.

Here is a crude animation illustrating the assumption that the two electrons are prepared, one in a spin-up, the other in a spin-down state. They remain in opposite states no matter how far they separate, provided neither interacts with anything else until the measurements at A and B.

Two "hidden constants" of the motion, one spin up, one down, might explain the fact of perfect correlations of opposing spins. That "Nature's" initial choice of up-down versus down-up is quantum random explains why the bit strings can be used in quantum encryption.

What Schrödinger told us in 1935 is that neither particle has a definite spin direction until a measurement is made of either particle. Schrödinger described the situation before measurement as in a linear combination (a superposition) of particle 1 spin up, particle 2 spin down and particle 1 spin down, particle 2 spin up.

The proper quantum description is that the two-particle wave function is in a linear combination of up-down and down-up states.

Ψ12 = 1/√2) | 1+2- > + 1/√2) | 1-2+ >

Just one of these two possible up-down (+ -) and down-up (- +) states can become actual when measured. The 1/√2 coefficient, when squared, tells us that the two states have probability 1/2.

The spin directions and spin values (perfectly correlated) for Alice and Bob do not appear until one of them makes a measurement. And only then if Alice and Bob both measure in the same, previously agreed upon, direction, as we will visualize below.

Note that while individual spin values and directions of the two particles are indeterministic before measurement, the joint or shared property of total spin zero is not indeterministic. While there is no information in this equation about the individual particle spins, the equation contains the certain information that if one particle is measured spin-down, the other must be found spin-up

Because the two-particle wave function Ψ12 has total spin zero, as Schrödinger showed, when they are disentangled and become the product of two single-particle wave functions Ψ1 and Ψ2, whichever of the two possible products of single-particle wave functions appears, up-down (+ -) or down-up (- +), both will continue to conserve total spin!

If Ψ1 is measured with spin up, then Ψ2 must have spin down in the exact opposite direction, conserving total spin (angular momentum). This lets us know that Ψ2 is spin down without measuring it. We believe that this should be called "knowledge-at-a-distance." There is no superluminal signaling, no physical influence, no "action-at-a-distance."

We describe this situation as a single "hidden constant" of the motion. The hidden constant is the total spin zero, a shared property of the two-particle wave function Ψ12. Spin is a constant because of the principle of conservation of angular momentum, based on the rotational symmetry of the two-particle wave function. And this "hidden" constant achieves everything the David Bohm and John Bell hoped their "hidden variables" could do!

The "Free Choice" of the Experimenter

We can establish the fact that there is no preferred spatial direction for the rotationally symmetric two-particle entangled wave function. The founders of quantum mechanics, especially Werner Heisenberg, insists that the experimenter has a "free choice" as to which direction (or component of spin) to measure. It is therefore Alice's "free choice" that introduces the preferred direction into the problem. And it is only measurements by Bob in that same (or opposite) direction that will yield the perfectly correlated (or anti-correlated) values needed for quantum encryption.

This preferred direction did not exist before Alice's measurement. And note that although Alice can choose the direction, she cannot choose the outcome, spin up or spin down. As Paul Dirac showed, the outcome is indeterministic, a matter of chance that he called "Nature's Choice."

There is no interaction or action-at-a-distance from Alice to Bob. When the two-particle Ψ12 collapses into disentangled Ψ1 and Ψ2, the new single-particle wave functions have opposite spins in the direction Alice chose to measure.

Here is a crude two-dimensional animation of this picture,

If you move the timeline playhead slowly you can see the two spins are oscillating back and forth, always keeping the total spin zero. Richard Feynman described them as arrows spinning randomly in all directions, but none of these visualizations do justice to the underlying fact that there is no preferred direction for the rotationally symmetric total spin zero state of the entangled Ψ12 wave function.

Principle Theories and Constructivist Theories

In his 1933 essay, "On the Method of Theoretical Physics," Albert Einstein argued that the greatest physical theories would be built on "principles," not on constructions derived from physical experience. His theory of special relativity was based on the principle of relativity, that the laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames, along with the constant velocity of light in all frames.

Our explanation of entanglement as the result of "hidden constants" of the motion is based on conservation laws, which, as Emmy Noether showed, are based on still deeper principles of symmetry.

This "principle" explanation is, of course, also based solidly on the empirical fact that electron spins are always experimentally (constructively) found in opposite directions.

Summary Explanation of Quantum Entanglement

As Einstein should have seen in his discussion with Leon Rosenfeld, the conservation of total zero momentum of identical particles separating with equal but opposite velocities does not depend on any interaction between the particles. Neither particle is "influencing" the motion of the other one to keep their momenta perfectly opposite. They each conserve their own momentum.

The case is similar with two quantum particles, whether electrons, photons, atoms, or "buckyballs. " The two-particle wave function Ψ12 describes the probability of finding the two particles somewhere if a measurement is made. As with any quantum wave function, particles can be found anywhere the squared modulus |Ψ2| is not zero.

Just as we can say nothing about where a single particle is located before measurement, so we cannot know where the two particles will be found when observed. But we can know that their relative spin directions will always be found to be exactly opposite one another, just as with Einstein's two particles with opposite linear momentum.

The perfect rotational symmetry of the two-particle wave function Ψ12 ensures that every direction angle is equally probable. As Werner Heisenberg and Pascual Jordan liked to describe it, the specific properties of particles are "created" by the measurement, when one of the possible locations and angle directions becomes actual. Alice's "free choice" of direction to measure ensures that the spin will be found along that angle direction, but randomly up or down in that direction, according to Paul Dirac's idea that this is "Nature's choice." As long as Bob measures at the same pre-agreed angle, he will always find his spin opposite to the direction that Alice found, establishing the perfect anti-correlation of bits needed for quantum encryption.

The proper quantum description is that the two-particle wave function is in a linear combination of up-down and down-up states.

Ψ12 = 1/√2) | 1+2- > + 1/√2) | 1-2+ >

Either of these possible states can become actual when measured. Both will conserve spin angular momentum, our "hidden constant of the motion."

We might attempt a rough visualization (Schrödinger's Anschaulichkeit) of the spins of the entangled particles. It is something like an ice-skating couple holding hands while they rotate around one another. But the analogy Is weak, because quantum spins are not in ordinary 3-dimensional space.

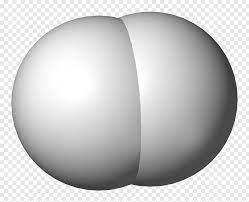

Below is a 3D visualization that demonstrates the rotational symmetry of two entangled atoms about their molecular axis, for example the hydrogen molecule made up of two hydrogen atoms. You can rotate the molecule to view it from a point on the molecular axis that is outside the molecule.

molecule by Eliam113 on Sketchfab Click on the play icon and rotate the H2 molecule in any direction. The ground state of the H2 molecule is a 1s2 1Σ+g singlet state with total spin angular momentum zero because the spins of the two electrons are always found in opposite directions.

We consider a molecule of total spin zero consisting of two atoms, each of spin one-half... The two atoms are then separated by a method that does not influence the total spin. After they have separated enough so that they cease to interact, any desired component of the spin of the first particle (A) is measured. Then, because the total spin is still zero, it can immediately be concluded that the same component of the spin of the other particle (B) is opposite to that of A.But the measurements by Alice and Bob must be made in the same direction (at the same pre-agreed upon angle) to preserve the symmetry and get that perfectly opposite outcome. We can visualize the positions of their Stern-Gerlach devices located on the extension of the molecule's internuclear axis. If you rotate the animation until you are looking along the internuclear axis, it looks like a perfect circle. In this position you see the rotational symmetry about that axis. If Alice measures "first" at angle α and Bob then measures at a different angle β, since Bohm tells us Bob's particle must be found oriented perfectly opposite at -α, Bob's measurements will be decorrelated by cos(β-α)2. Note that the rotational symmetry about the internuclear axis means that this result happens whichever angle Alice starts with. In experimental terms, the fact that the results don't depend on Alice's choice of angle together with the observed cos(β-α)2 decorrelation seen in all the Bell experiments proves (confirms) that the two-particle wave function is symmetric about the inter-particle axis. which is the flight path of the separating particles. If Bob measures at a different angle from Alice, this destroys the rotational symmetry. As Bohm warned, this would influence the total spin of the two particles, which would no longer be zero. But that would not violate conservation of angular momentum, because the spin of the two Stern-Gerlach devices would also be changed, exactly conserving the combined total angular momentum of the particles and the measurement devices.

Response to Criticisms of Our Explanation of Quantum Entanglement

Critics say that we mistakenly assume that the entangled particles acquire their (perfectly correlated) properties (spin values, positions) before Alice's or Bob's measurement. We don't. We agree their individual properties are indeterministic. But we insist that their shared property of total spin zero (our "hidden constant") is determined by their initial entanglement.

The Copenhagen Interpretation and many others agree that quantum properties (spin, position, momentum) normally do not exist before their measurement. (Exceptions are cases of a "state preparation" where a system is put into a definite state. A subsequent measurement finds it in the same state - Pauli measurements of the first kind.) The initial entanglement is such a state preparation.

Properties acquired during a measurement are cases in which we say that the observer "creates reality." And we agree that Alice's measurement of spin-up or spin-down in some direction did not exist before her measurement. It was truly random. Dirac calls it Nature's choice". But note that her choice of measurement direction (angle) was her own (Heisenberg's "free choice").

Alice is creating the reality of the spin in her chosen direction. Bob will only get a perfectly correlated (or anti-correlated) result if he measures at exactly the same angle (by pre-agreement with Alice). Only in this case can Alice and Bob generate the correlated sequences of random bits needed for quantum cryptography.

So we agree with our critics who say the specific properties created by Alice and Bob (spin and direction angle) do not pre-exist their measurements. However, the critics are also correct that our explanation does require something to exist before the measurements. But what pre-exists is not individual particle properties.

It is instead the shared or joint property of total spin angular momentum zero that the entangled particles acquired when they were initially entangled, and which they carry with them as they travel. We describe this shared property as a "hidden constant of the motion" because it functions just like the "hidden variables" that David Bohm and John Bell hoped for.

We believe this "hidden constant" fully explains the non-local behavior of entangled particles and the apparent violation of relativity.

The "hidden constant" for entangled particles is the total spin zero state the particles are in. Without any external interaction (or decoherence by the environment), the total spin remains zero at all times by the law of conservation of angular momentum.

Critics are correct that we do not know (epistemology) and the particles do not have (ontology) specific spin directions or positions. But we do know, and the particles do have, the joint or shared property of total spin zero at all times. (The two-particle wave function Ψ12 is rotationally symmetric, a symmetry that underlies the conservation of angular momentum, according to Emmy Noether.)

Specifically, conservation of momentum laws mean that just before the measurement, whatever the unknown spins and positions of the entangled particles, their spins are always exactly opposite to one another, and whatever the unknown positions of the particles, they are equidistant from and on opposite sides of the initial entanglement, as Einstein described to Leon Rosenfeld in 1933 and the 1935 EPR authors called "elements of reality" and a "paradox."

Again, although we do not know those spins and directions, because they are ontologically indeterminate,

the fact that at the instant of Alice's measurement Bob's particle must have exactly opposite properties is not because an "influence" travels from Alice to Bob faster than the speed of light (Einstein's "spooky action at a distance"). It is because the particles must have opposite momenta when measured because the total momentum is prepared to be zero and remains zero at all times up to and including their measurements.

If without any external interaction the conservation of angular momentum law were violated at some moment, it would be a much greater problem for physics than entanglement itself, however mysterious and puzzling entanglement may seem.

We are surprised that Einstein did not notice this fact. When Bohr, Kramers, and Slater suggested in 1924 that the conservation laws might only be statistically conserved, Einstein immediately suggested the experiment (to Hans Geiger) that would disprove the BKS hypothesis and confirm the conservation principles that are fundamental to both classical physics and quantum physics.

References

The Ground State of the Hydrogen Molecule, Journal of Chemical Physics, 1933, vol. 1, p.825.

Erwin Schrödinger, Discussion of Probability between Separated Systems (Entanglement Paper), Proceedings of the Cambridge Physical Society 1935, 31, issue 4, pp.555-563

David Bohm, A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of "Hidden" Variables. I

David Bohm, A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of "Hidden" Variables. II

David Bohm and Yakir Aharonov, Discussion of Experimental Proof for the Paradox of Einstein, Rosen, and Podolsky

John Bell, On the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Paradox

"Albert Einstein, On the Method of Theoretical Physics," The Herbert Spencer Lecture, Oxford, June 10, 1933, Ideas and Opinions, Bonanza Books, 1954, pp.270-276; original German in Mein Weltbild, Amsterdam, 1934, (PDF)

For Teachers

For Scholars

|