Plato in the

Theaetetus (200D-201C) defined knowledge as

justified true belief. Justification was providing some reasons (λόγος or συλλογισμῶ), a rational explanation for the belief. True opinion

accompanied by reason is knowledge. (δόξαν ἀληθῆ μετὰ λόγου ἐπιστήμην εἶναι) (202C)

Although "justified true belief" is the traditional philosophical definition of knowledge, still in use in modern positions on epistemology, the ancients were already skeptical of this Platonic idea. Socratic dialogues normally did not reach any positive conclusions; they were "negative dialectics."

Indeed, the Theaetetus ends with Socrates' utter rejection of perception, true belief, or true belief combined with reasons or explanations as justification. Socrates says:

And it is utterly silly, when we are looking for a definition of knowledge, to say that it is right opinion with knowledge, whether of difference or of anything else whatsoever. So neither perception, Theaetetus, nor true opinion, nor reason or explanation combined with true opinion could be knowledge (epistéme).

καὶ παντάπασί γε εὔηθες, ζητούντων ἡμῶν ἐπιστήμην, δόξαν φάναι ὀρθὴν εἶναι μετ᾽ ἐπιστήμης εἴτε διαφορότητος εἴτε ὁτουοῦν. οὔτε ἄρα αἴσθησις, ὦ Θεαίτητε, οὔτε δόξα ἀληθὴς οὔτε μετ᾽ ἀληθοῦς δόξης λόγος προσγιγνόμενος ἐπιστήμη ἂν εἴη.

Plato's Theaetetus, (210A-B)

An infinite regress arises when we ask what are the justifications for the reasons themselves.

If the reasons count as knowledge, they must themselves be justified with reasons for the reasons, and so on,

ad infinitum.

The problem of the infinite regress was a critical argument of the Skeptics in ancient philosophy.

Sextus Empiricus tells us there are two basic Pyrrhonian modes or tropes that lead the skeptic to suspension of judgment (ἐποχῆ):

They [skeptics] hand down also two other modes leading to suspension of judgement. Since every object of apprehension seems to be apprehended either through itself or through another object, by showing that nothing is apprehended either through itself or through another thing, they introduce doubt, as they suppose, about everything. That nothing is apprehended through itself is plain, they say, from the controversy which exists amongst the physicists regarding, I imagine, all things, both sensibles and intelligibles; which controversy admits of no settlement because we can neither employ a sensible nor an intelligible criterion, since every criterion we may adopt is controverted and therefore discredited.

And the reason why they do not allow that anything is apprehended through something else is this: If that through which an object is apprehended must always itself be apprehended through some other thing, one is involved in a process of circular reasoning or in regress ad infinitum. And if, on the other hand, one should choose to assume that the thing through which another object is apprehended is itself apprehended through itself, this is refuted by the fact that, for the reasons already stated, nothing is apprehended through itself. But as to how what conflicts with itself can possibly be apprehended either through itself or through some other thing we remain in doubt, so long as the criterion of truth or of apprehension is not apparent, and signs, even apart from demonstration, are rejected.

(Outlines of Pyrrhonism, Loeb Library, R.G.Bury tr., 1.178-79)

The skeptic can always ask a philosopher for justifying reasons. When those reasons are given, he can demand their justification, and this in turn leads to an infinite regress of justifications.

The endless controversy and disagreement of all philosophers cautions us against accepting any of their arguments as knowledge. It is said by some that philosophy has been two thousand years of failed attempts to refute these skeptical arguments.

Second only to

Kant 's "scandal" that philosophers cannot logically prove the existence of the external world, it is scandalous that professional philosophers to this day are in such profound disagreement about what it means to know something.

Epistemologists may not all be wrong, but with their conflicting theories of knowledge, how many of them are likely to be right?

This is especially dismaying for those epistemologists who still see a normative role for philosophy that could provide an

a priori foundation for scientific or empirical

a posteriori knowledge. Kant called this the

synthetic a priori.

In recent years, professional epistemologists have been reduced to quibbling over "

Gettier problems" - clever sophistical examples and counterexamples that defeat the reasoned justifications for true beliefs.

Following some unpublished work of Gregory O'Hair,

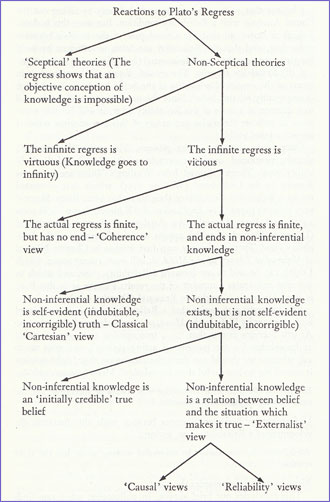

David Armstrong identifies and diagrams several possible ways to escape the Skeptic's infinite regress, including:

- Skepticism - knowledge is impossible

- The regress is infinite but virtuous

- The regress is finite, but has no end

(Coherence view)

- The regress ends in self-evident truths, the axioms of geometry, for example

(Foundationalist view)

- Non-inferential credibility, such as direct sense perceptions

- Externalist theories (O'Hair is the source of the term "externalist")

- Causal view (Ramsey)

- Reliability view (Ramsey)