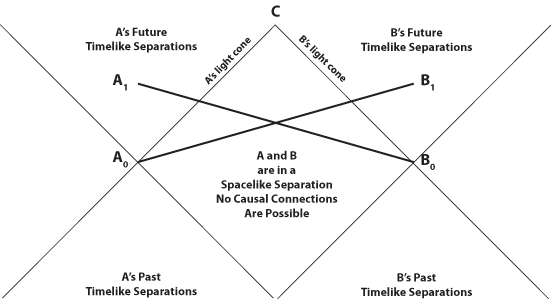

But this is not a transitive relation. Just because A sees B1 as his "now" at A0 and B sees an event A1 in A's future as B's "now" does not make the event in A's future "now" for A. It does not prove that "the future is now."

For B at B0 to affect A at A1, the "influence" would have to move faster than the speed of light.

But this is not a transitive relation. Just because A sees B1 as his "now" at A0 and B sees an event A1 in A's future as B's "now" does not make the event in A's future "now" for A. It does not prove that "the future is now."

For B at B0 to affect A at A1, the "influence" would have to move faster than the speed of light. A and B are in a spacelike separation. The earliest possible moment that they could affect one another is if they traveled at the speed of light to meet at C. The first philosopher to consider whether special relativity could prove determinism was J. J. C. Smart. Smart was a determinist. In 1961, his article in Mind developed the logical standard argument against free will. In 1964, he discussed Hermann Minkowski's 1908 argument for a special-relativistic block universe. Minkowski's work could be interpreted as a "tenseless" view of space-time that says "the future is already out there." Everything that is going to happen has already happened, an idea called actualism.

Minkowski's Block Universe

Minkowski says his argument is entirely mathematical, though based on experimental physics,

The views of space and time which I wish to lay before you have sprung from the soil of experimental physics, and therein lies their strength. They are radical. Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality. First of all I should like to show how it might be possible, setting out from the accepted mechanics of the present day, along a purely mathematical line of thought, to arrive at changed ideas of space and time...Three-dimensional geometry becomes a chapter in four-dimensional physics.Minkowski introduces his fundamental axiom:

c2dt2 - dx2 - dy2 - dz2 > 0,

or what comes to the same thing, that any velocity v always proves less than c. Accordingly c would stand as the upper limit for all substantial velocities, and that is precisely what would reveal the deeper significance of the magnitude c. In this second form the first impression made by the axiom is not altogether pleasing. But we must bear in mind that a modified form of mechanics, in which the square root of this quadratic differential expression appears, will now make its way, so that cases with a velocity greater than that of light will henceforward play only some such part as that of figures with imaginary co-ordinates in geometry.

J. J. C. Smart

In the introduction to his 1964 book, Smart was not yet committed to the tenseless view of space-time he holds today. In 1964 he was agnostic as to whether "some sort of fatalism must be true" and the future must already exist. He emphasizes the mathematical nature of the work, that space-time is not an ordinary space, and that the four-dimensional picture does not imply determinism.

We must not forget that space-time is a space in the mathematical sense of the word. Quite clearly it cannot be space in the sense of something which endures through time. This is sometimes half-forgotten in popular expositions of relativity. It is sometimes said, for example, that a light signal is propagated from one part of space-time to another. What should be said is that the light signal lies (tenselessly) along a line between these two regions of space-time. Moritz Schlick has expressed this point well when he says: "One may not, for example, say that a point traverses its world-line; or that the three-dimensional section which represents the momentary state of the actual present, wanders along the time-axis through the four-dimensional world. For a wandering of this kind would have to take place in time; and time is already represented within the model and cannot be introduced again from outside." And if there can be no change in space-time, neither can there be any staying the same. As Schlick points out, it is an error to claim that the Minkowski world is static: it neither changes nor stays the same. Changes and stayings the same can both of course be represented within the world picture, for example a changing velocity by a curved line and a constant velocity by a straight line. The tenseless way of talking which is appropriate to the four-dimensional space-time world seems to suggest to some people that some sort of fatalism must be true, and that the future is already somehow "laid up." This, however, is a confusion, for the "is" in "is already laid up" is a tensed one and suggests that the future exists now, which is absurd. The event of the future, like those of the past, certainly exist, in the sense in which this verb is used tenselessly, but of course they do not exist now. Nor does the four-dimensional picture imply determinism. It is quite neutral between determinism and indeterminism. The issue between determinism and indeterminism can be put quite easily in the language of space-time. lt is as follows: From a complete knowledge of a certain three-dimensional (spacelike) slice of space-time together with a knowledge of the laws of nature, could the properties of later (and indeed earlier) slices of space-time be deduced? For present purposes let us be agnostic as to the answer to this question.

C.W. Rietdijk

Two years later, C.W. Rietdijk and Hilary Putnam were not so cautious about proving determinism using special relativity.

Rietdijk was unequivocal. His article in the journal Philosophy of Science was titled "A Rigorous Proof of Determinism Derived from the Special Theory of Relativity." He says,

A proof is given that there does not exist an event, that is not already in the past for some possible distant observer at the (our) moment that the latter is "now" for us. Such event is as "legally" past for that distant observer as is the moment five minutes ago on the sun for us (irrespective of the circumstance that the light of the sun cannot reach us in a period of five minutes). Only an extreme positivism: "that which cannot yet be observed does not yet exist", can possibly withstand the conclusion concerned. Therefore, there is determinism, also in micro-physics.

Hilary Putnam

One year after Rietdijk, the "realist" philosopher Putnam was ready to prove that future events are already real! [his exclamation]

Putnam says that his argument is remarkable,

(1) All (and only) things that exist now are real. Future things (which do not already exist) are not real (on this view); although, of course they will be real when the appropriate time has come to be the present time. Similarly, past things (which have ceased to exist) are not real, although they were real in the past. If we assume classical physics and take the relation R to be the relation of simultaneity, then, on the view (1), it is true that all and only the things that stand in the relation R to me-now are real. We now discover something really remarkable. Namely, on every natural choice of the relation R, it turns out that future things (or events) are already real!

Roger Penrose

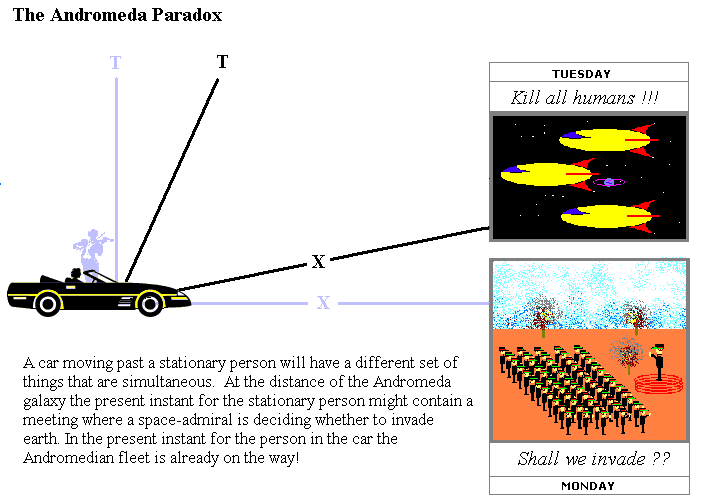

In 1989, in his book The Emperor's New Mind, Roger Penrose developed an intergalactic form of the Rietdijk - Putnam argument to prove the universe is pre-determined for special relativistic reasons.

He describes the situation:

He describes the situation:

"Two people pass each other on the street; and according to one of the two people, an Andromedean space fleet has already set off on its journey, while to the other, the decision as to whether or not the journey will actually take place has not yet been made. How can there still be some uncertainty as to the outcome of that decision? If to either person the decision has already been made, then surely there cannot be any uncertainty. The launching of the space fleet is an inevitability." The observers cannot see what is happening in Andromeda. It is light-years away. The paradox is that they have different ideas of what is happening "now" in Andromeda.

Michael Lockwood

In his 1989 book, Mind, Brain, and the Quantum: the Compound 'I', Michael Lockwood denies the openness of the future, which is "already out there." subscribes to this view.

Time has become a fourth dimension; and an individual persisting object, such as a human body, is to be conceived as a four-dimensional 'worm', laid out in space-time, each three-dimensional time-slice of which corresponds to the object as it is at a particular moment in its history. (The set of space-time points occupied by this 'worm' — if one ignores the fact that it has spatial thickness as well as temporal length — is known as the object's world-line.) In this conception there is no universal march or flow of time. There cannot be, because there is no universal present; and consequently there is no universal past or future... This makes trouble, incidentally, for a conception of time that many philosophers from Aristotle to the present day have wished to defend, according to which the future is open, partially undefined, in contrast to the past, which is fixed, closed, a fait accompli. The motivation for such a view lies mainly in a desire to defend free will, to enable us to regard the future (in words I once saw in the Reader's Digest) as 'not there waiting for us, but something we make as we go along'. In the context of relativity (as is pointed out by Hilary Putnam), such a view appears not so much false as meaningless.

Michael Levin

In a 2007 article in the Journal of Philosophy, Michael Levin Michael Levin defends compatibilism against the charge that special relativity implies what he calls relativistic fatalism.

The notion that special relativity can show that the world is deterministic was first proposed by the philosophers C. W. Rietdijk and Hilary Putnam in the 1960's. J.J.C.Smart described a "block universe," in which all space-time events already exist, as a "tenseless" deterministic universe.

Levin cites Michael Lockwood's 2005 book, The Labyrinth of Time, as arguing "with new vigor that the Special Theory of Relativity rules out free will."

Lockwood argues that this is not just a case of causal determinism denying free will. Special relativity, he says, challenges the very notion of cause. If the future is already out there, Lockwood says, causality has little to do with it.

Levin disagrees. He says that special relativity (SR) has room for cause and effect.

Relativistic fatalists...are certainly not compelled to renounce causality by SR alone, which respects standard conditions on the time order of cause and effect. They may therefore find it less disruptive to adopt a non-Aristotelian account of causality consonant with SR, such as energy transmission, and confront compatibilism restated in its terms. Moreover, denial of causality wars with their larger goal, shared by all fatalists, of showing that people are far more constrained than ordinarily supposed. If nothing is causally impossible — causality being an illusion — people are less constrained than ordinarily supposed. From the fatalist's own viewpoint, Lockwood's argument proves too much.

The basic idea of using the special theory of relativity to prove determinism is that time can be treated mathematically as a fourth dimension. This gives us excellent results for experiments on moving objects and explains the strange Lorentz contraction of objects in space and dilations of clock speeds for observers in fast moving frames of reference (coordinate systems). But these philosophers jump to the unacceptable conclusion that the time dimension is like space and so the "future is already out there," any event that is going to happen has already happened. This is the concept of actualism, that only what actually happens ever could have happened.. Just because an event is placed on a space-time diagram, it is not made actual. It is still in the future. Quantum mechanics has eliminated the physical determinism that Laplace's demon might have used to connect present events causally with events in the future. Einstein was a confirmed determinist. He might have been surprised to know that so many philosophers attempt to use his theory of special relativity to prove determinism. Einstein believed in determinism as much any scientist. If the special theory of relativity could be used to "prove" determinism, he likely would have. He did not. He probably knew that it is an absurd argument, an exercise in logic and language, and knew it would fail. But Einstein's special relativity has one more important role to play, in the problem of nonlocality and entanglement, which some philosophers connect to problems of consciousness and free will.

Nonlocality and Special Relativity

The mysterious phenomenon exhibited in the famous Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen experiments is the apparent transfer of something physical faster than the speed of light.

What information philosophy sees that happens actually is merely an instantaneous change in the information about probabilities (actually complex probability amplitudes).

The idea of something measured in one place "influencing" measurements far away challenged what Einstein thought of as "local reality." It came to be known as "nonlocality." Einstein called it "spukhafte Fernwirkung" or "spooky actions at a distance."

Einstein had objected to nonlocal phenomena as early as the Solvay Conference of 1927, when he criticized the collapse of the wave function in the two-slit experiment as "instantaneous-action-at-a-distance" that prevents the wave from acting at more than one place on the screen.

Here is an animated explanation of what happens in the two-particle wave-function collapse at the heart of nonlocality.

Animation of a two-particle wave function collapsing - click to restart

Animation of a wave function collapsing - click to restart